Building Infrastructure the American Way

The chief problem with industrial policy, as I noted in my last post, is less economic than political: with the government handing out investment money, there is a big danger that it will be allocated not on the basis of likely economic returns, but as a form of patronage by politicians. This has been the Achilles’ heel of all state-owned enterprises, which tend to prioritize jobs for political supporters over profits.

If the Biden administration is serious about its infrastructure initiative and is actually able to get some money out of Congress to support it, it will have to think carefully about two big issues. The first concerns allocating these funds in a rational way, and the second regards clearing away the enormous amounts of red tape that surround such projects today.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

There is no question that America faces a huge infrastructure deficit. The American Society of Civil Engineers publishes a regular estimate of the funding gap between the country’s needs and its actual spending; the latest figure is $5.6 trillion. The poor state of the country’s roads, airports, and bridges is evident to anyone traveling into the US from Europe or Asia. Infrastructure is a classic public good on which there is at least theoretical bipartisan agreement that something needs to be done. Yet there is also a bipartisan conspiracy to prevent this from happening: Republicans don’t want to spend taxpayer money to fix the problem, and Democrats want to permit projects to death.

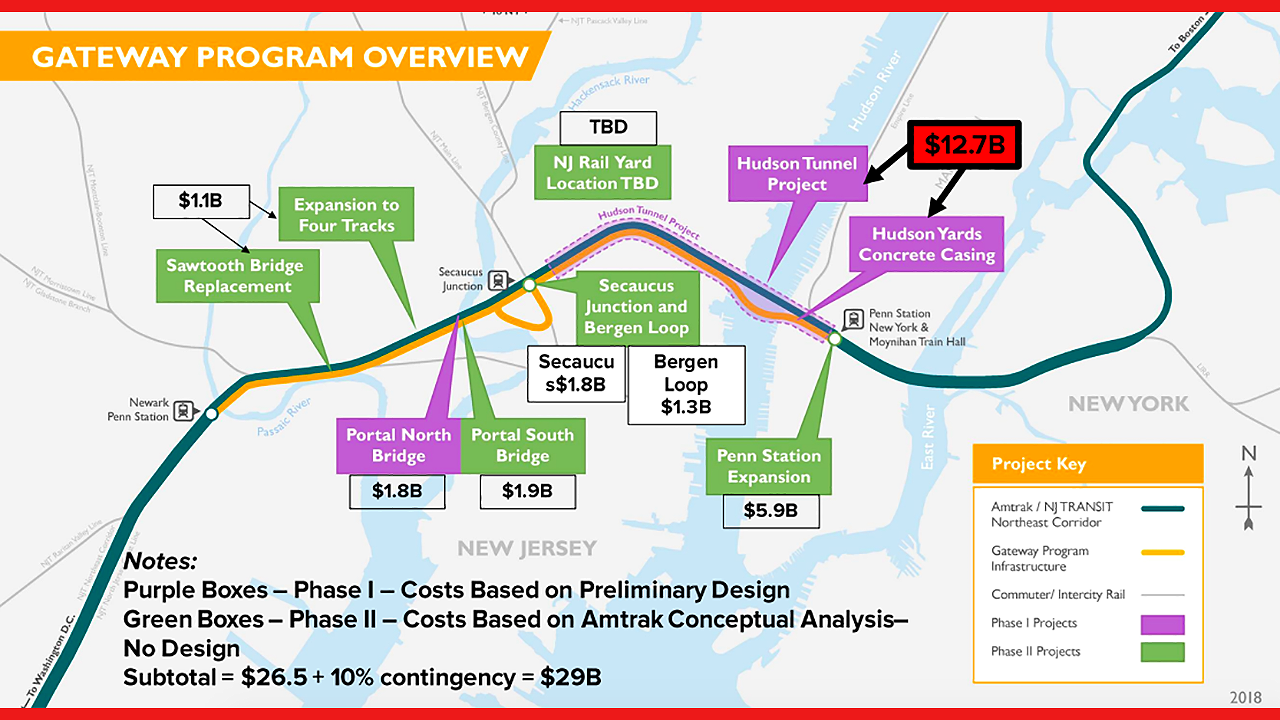

The Trump administration came into office promising to fix the problem, but then became a textbook case of how not to invest in infrastructure. Trump saw such spending as a way of rewarding friends and punishing enemies. At the end of the Obama administration, there had been agreement between the State of New York and the federal government to jointly fund the Gateway Program that would revitalize the Northeast Corridor by, among other things, putting a new tunnel under the Hudson River to connect New York and New Jersey. The Trump administration changed the cost-sharing formula in a way that made it unviable, with the strong suspicion that this was done to get back at Governor Andrew Cuomo and the Democrats controlling that state’s politics.

Despite Congress refusing to allocate money for his border wall, Trump moved Defense Department construction funds to do just that. Time will doubtless uncover more instances of the politicized allocation of infrastructure resources in that administration.

Other liberal democracies have come up with much better ways of making such decisions, ones that take them out of the hands of politicians with their short-term calculations. Australia, for example, has a federal office staffed by career bureaucrats who compile a list of major infrastructure proposals across the entire nation, then prioritize them in terms of economic impact, alignment with national priorities, and deliverability. Politicians control the final spending decisions, but rely heavily on the advice of Infrastructure Australia.

The United States doesn’t do things this way. Infrastructure has always been a classic venue for pork-barrel politics, and in the days of earmarks was the place where legislation would get done by throwing in a bridge or a convention center into the mix to buy the necessary votes to pass legislation. I remember going up from Norther Virginia periodically to visit my mother in an assisted care facility in State College, Pennsylvania, and returning on Interstate 99, the “Bud Shuster Highway,” that connected State College to Altoona.

It was a beautiful modern expressway that never had any cars on it. It never connected any major population centers, and actually violated the national Interstate numbering system. The only reason it existed was because Bud Shuster was the powerful chairman of the House Transportation Committee responsible for writing funding bills, and this highway ran through his district.

President Biden’s infrastructure plan, announced in early April as part of his “American Jobs Plan,” is admirable in many ways. Like his stimulus package, it is big and ambitious at $1.9 trillion, a number that actually is in the ballpark of what needs to be spent. His new Transportation Secretary, Pete Buttigieg, as well as Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo and Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, have been tasked with lobbying for the package and helping it get through a skeptical Congress.

It is not clear, however, that formulation of whatever bill finally emerges will reflect anything like a rational process of setting national priorities. Announcement of the initiative has opened up an unseemly scramble in Washington to stuff every politician’s favorite project into the bill. Biden will not politicize spending in the manner of Trump, having projects go only to favored blue states that supported him in the election. The Democrats have other ways of politicizing infrastructure bills, however, by using them to achieve other social policy goals like lifting minority employment or encouraging female-owned businesses, or disguising environmental legislation as infrastructure spending. Republicans have already criticized the proposal as stretching the definition of infrastructure to include things like support for home care workers or worker retraining.

This is not to say that a massive spending bill like the one proposed cannot seek to accomplish multiple objectives at the same time. It would be crazy to spend this amount of money and not take the energy transition into account. We don’t need to build more pipelines and coal-fired power plants. The issue is rather different: there needs to be a national plan that lays out competing objectives, and sets clear priorities that allow taxpayers to see the tradeoffs that are being made. Adding requirements for minority or union hiring, or further environmental checkoffs, will delay and sharply increase the cost of new projects in ways that will not be apparent until after the fact. Maybe they're worth it, but it would help to know their cost in advance.

This brings us to the second challenge, which has to do with red tape. Already, infrastructure projects are mired in an arcane process by which upwards of fifteen federal agencies have to give their approval, approvals which have to be granted sequentially rather that simultaneously. If an agency makes an objection towards the end of the queue, the entire process needs to start over from the beginning. And this is just the federal part; in many states there is a duplicative process that repeats these certifications through a set of state agencies. Under the California Environmental Quality Act, every citizen of the state has standing to sue any given project anonymously, with no statute of limitations.

The United States will never be able to move to a rational resource-allocation process for infrastructure like that of Australia. It might be nice in theory to create an Infrastructure Bank which we could rely on for vetting projects and recommending priorities. But the U.S. Constitution locates responsibility for spending in Congress, and getting any sort of legislation out of that polarized body has always required messy compromises and payoffs. Indeed, many observers of Congress have suggested that the abolition of earmarks was a mistake, and that we need to return to some version of pork barrel politics if we are to get anything done in the future.

Nonetheless, if the Biden administration is serious about fixing American infrastructure and using this spending to stimulate job creation and productivity growth, it needs to address the administrative process under which proposals are vetted and implemented. There are many easy gains in this realm that could be taken to simplify and speed up approvals, without sacrificing the environmental and social goals that everyone agrees are desirable. The big danger right now is that desire to accomplish these non-economic objectives will add a further layer of rules and checkoffs to an already burdensome and self-undermining process.

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe