Finally, a Nation

There’s a balance between the stories of 1776 and 1619, and looking to the Civil War can help us find it.

In his President’s Day American Purpose essay, “1619 vs. 1776,” Daniel Chirot writes that the problem with America’s traditional historical narrative, grounded in 1776, “was that it left out too many contradictions and exceptions.” The New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, released in August 2019, focused on these contradictions and exceptions, claiming that the country’s “true birthdate” was 1619, when the first African slaves (more properly, indentured servants) arrived on America’s shores. But the 1619 Project is, to say the least, an overcorrection.

The clash between the two dates is more than academic. As historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., noted in The Disuniting of America (1991), a “nation denied a conception of its past will be disabled in dealing with its present and its future.” When our stories about ourselves fracture, so will we. In the years to come, our differences—racial, religious, cultural, and political—stand to grow deeper still. If this newfound flourishing of differences is not to tear us apart, it must be bounded by widespread agreement on certain fundamentals—a civic creed—while allowing for legitimate variations and disagreements. For that, we need more than ideas and principles. We need stories that give them life. We need history not to erase most of those differences, but to find a way to live with them.

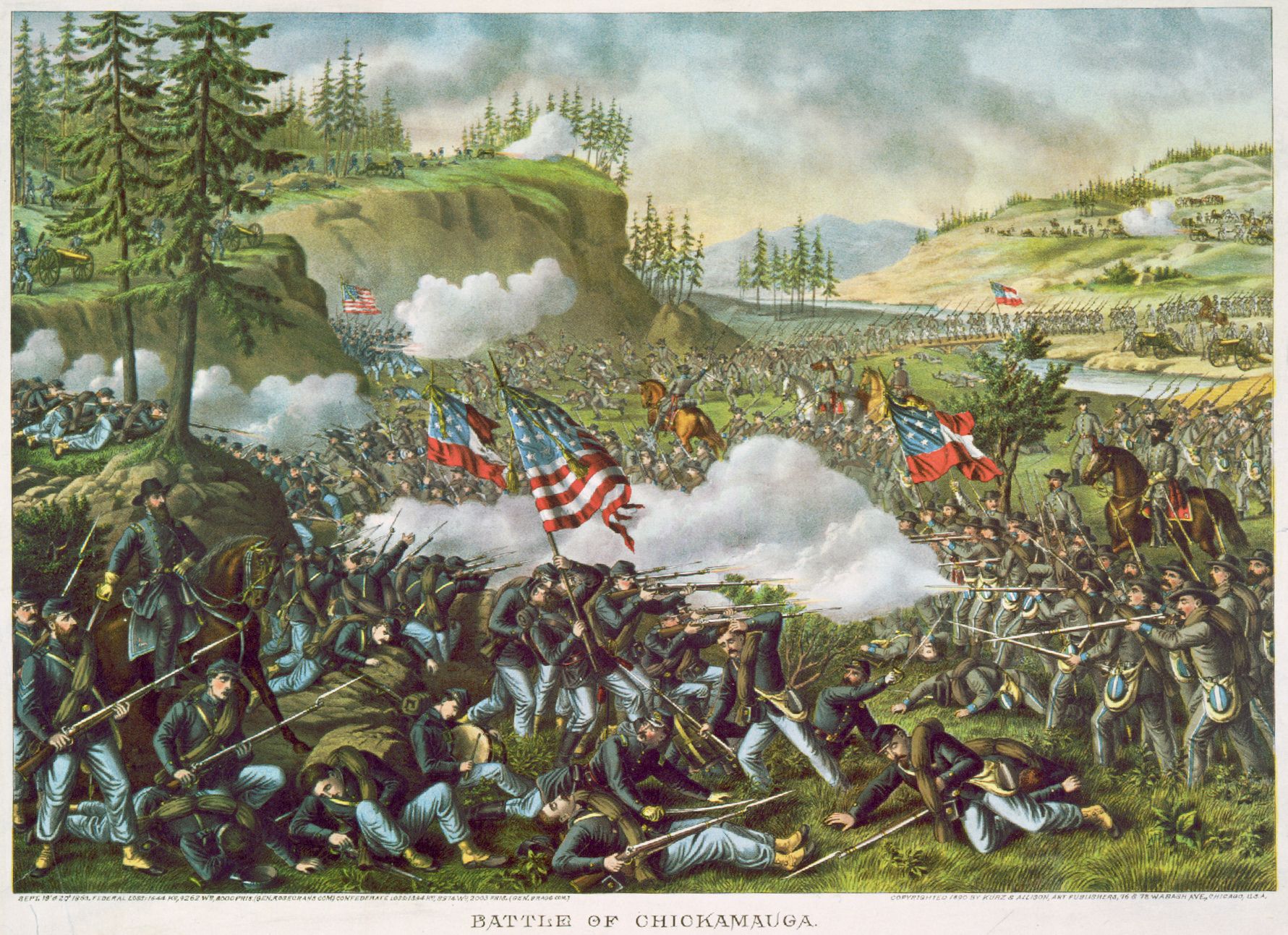

Thankfully, there is such a national story, grounded not in 1619 or 1776 but in 1865. Scholars like Columbia University’s Eric Foner refer to the close of the Civil War as our “second founding.” Before President Lincoln’s stand against Southern secession, the very nature of our national Union was contested: Were the United States a compact of separately sovereign states, or was the United States a single nation embodying a single people? The blood spilled in the Civil War put these questions to rest. The abolition of African-American chattel slavery sparked America’s final acceptance of its shared nationhood. Only with slavery abolished and secession defeated did the United States become a singular noun rather than a plural one.

An 1865-centric American narrative asserts that the American nation-state emerged from conflict and has been marked by conflict ever since. We are defined by neither “liberal consensus” nor white supremacy but by the story of how we cope with our differences. Much of American life is marked not by rooting out differences but by living together amid them.

In focusing on this American story, we do not have to choose between egalitarian democracy and racist slavocracy. We can see ourselves not as the embodiment of racial oppression or a quixotic search for some future ideal state of equal liberty, but as the continuing enterprise of navigating diversity, embracing differences that are acceptable, and suppressing those that are not.

What happened in April 1865 at Appomattox Court House vindicated American nationhood and began the project that continues—haltingly, imperfectly—until today.

Not-So-United States

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, American national identity was still in flux. People considered themselves Virginians, Southerners, New Englanders, or New Yorkers before they thought of themselves as Americans. The Union, as historian Kenneth Stampp has observed, was “widely perceived as an experiment whose future was at best uncertain.” It would take the Civil War, “a fight over American national identity” in the words of Francis Fukuyama, to actually forge a veritable American nation.

At the outset, the Revolutionary War was not a collective assertion of American national identity or fought out of a desire for national self-government. As Princeton historian John Murrin put it,

The American Revolution was not the logical culmination of a broadening and deepening sense of separate national identity emerging among the settlers of North America.… The seventeenth century created, within English America alone, not one new civilization on this side of the Atlantic, but many distinct colonies that differed as dramatically from one another as any of them from England.

During the fighting, writes Murrin, Americans often “discovered that they really did not like each other very much.” Anti-New England sentiments proved especially strong, sometimes materially hampering the war effort itself.

Colonists’ political identities at the time were partly grounded in their shared British identity. With their successful war, they did not exchange that British identity for a shared American identity, but fell back on their colonial, now state, identities. Indeed, David Hendrickson, in Peace Pact: The Lost World of the American Founding (2003), calls the Revolutionary struggle and even the making of the Constitution an “experiment in international cooperation.” Many rank-and-file colonists assumed that, after the war, their respective colonies would become completely independent of one another. In the 1783 Treaty of Paris, Britain called the United States “free sovereign and independent states.”

The Articles of Confederation were a sign of the weakness of the affective ties of American nationhood. Article III established the Confederation as a “firm league of friendship” among sovereign states. The Articles constituted what Gordon Wood has termed an “alliance not altogether different from the present-day European Union.” Even while the American economy and governmental stability foundered under the Articles, a more nationalist constitutional alternative was not the preordained solution. George Washington feared a thirteen-way dissolution of the nascent Union. James Madison worried about a regional breakup of the American confederacy.

Even the Constitution of 1787, nationalist-leaning and anti-populist, did not establish a firm sense of shared nationhood in the minds of most Americans. The states-centric rhetoric of small-state delegates at the Philadelphia Convention and of Anti-Federalists in the state ratifying conventions indicates that acceptance of a shared nationhood was not a consensus position. Historian and constitutional scholar Kevin Gutzman notes that most of the delegates to Virginia’s 1788 ratification convention understood each state as a “legally distinct entity from the other American states.… Virginians understood themselves to be entering into a compact/contract with the other parties: the other states. The states were primary, the federal relationship a convenience.”

Essential Differences

The absence of a uniform American political community shone through the 1798 Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions against the John Adams Administration’s Alien and Sedition Acts. Writing the Kentucky Resolution, Thomas Jefferson declared that “whensoever the General Government assumes undelegated powers,” the sovereign states had the right to declare “its acts … unauthoritative, void, and of no force.”

Within a few years, Jeffersonian talk of nullification was mirrored in Federalist talk of secession. Writing to Rufus King in 1804, former Secretary of State and ardent Federalist Timothy Pickering of Massachusetts lamented the rule of President Thomas Jefferson, that “cowardly wretch” and “Parisian revolutionary monster.” This was not idle talk from a losing, disgruntled politician. Pickering advocated secession by the “five New England States, New York, and New Jersey,” which would result in “practicable harmony and a permanent union.” Pickering’s talk of secession gained steam during the War of 1812. In 1814, disaffected Federalists convened in Hartford, Connecticut, to pass resolutions condemning the war effort, pushing back on the federal government’s authority to conduct it, and even hinting at secession if their resolutions proved “unsuccessful.”

With the end of the War of 1812 and of the Federalist dissent, the North-South chasm over slavery widened, providing glaring new examples of a weak sense of affective national ties. The explosion of plantation slavery induced by the cotton gin and U.S. territorial expansion in fulfillment of America’s “manifest destiny” to span the continent exacerbated the conflicts over the nature of the American union. The story of the South’s rejection of the Union is well known, but it is important that the roots of this rejection lay in Southerners’ contention that, although the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 indicated otherwise, the federal government had no power to restrict slavery’s spread into new federal territories. The separate states, in this view, retained ultimate sovereignty; the federal government was merely the states’ agent. The territories, argued South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun, were “the common property of the States;” and no “portion” of that Union could rightfully “proscribe the citizens of other portions of the Union from emigrating with their property to the Territories of the United States.” Property included slaves.

Thus, the rejection of a national political community lay at the root of the boiling interregional tension over slavery. “To express it more concisely,” Calhoun wrote in his posthumous 1851 Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States, the U.S. government is “federal and not national, because it is the government of a community of States, and not the government of a single State or nation.” Southerners were joined by a number of Northern allies, like Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas, in rejecting a singular national political community. As historian Michael Les Benedict described the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates, while Lincoln “spoke in terms of a national community,” Douglas “conceived of the states as the constituent elements of the Union.”

Although antebellum nationalists like Chief Justice John Marshall grounded the advent of American nationhood in the making of the Constitution, the reality is that the question of whether the Constitution had indeed created a nation was still very much up for debate until the Civil War and the subsequent Reconstruction Amendments. Even mainstream anti-slavery Northerners openly questioned whether the Constitution had indeed spawned a nation prior to the war.

During the 1819–20 Missouri Crisis—the first of many convulsions over the spread of slavery spawned by rapid territorial expansion—Northern Congressmen like Massachusetts’ Timothy Fuller implicitly placed the Southern states outside the framework of the U.S. Constitution and, thus, the nation. Pointing to the guarantee in the Constitution’s Article IV, Section 4, of a “Republican Form of Government” in every state, Fuller argued that the federal government’s barring of slavery in soon-to-be-admitted states was a constitutional requirement because “slavery in any State is so far a departure from republican principles.” In other words, those states still recognizing the legality of slavery were operating extra-constitutionally. But if the Constitution defined the nation, how could there be a nation if the practice in half of the national polity flew directly in the face of that definition?

George Will, in Statecraft as Soulcraft, wrote that a “democratic society presupposes only minimal consensus as to the common good; but it presupposes consensus nonetheless.” Was there “consensus” in the late 18th century between Philadelphians who had founded in 1775 “the first anti-slavery organization in history, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage,” and white South Carolinians who would go on to build a massive slave society full of forced black labor camps? There was not.

The Constitution sidestepped the issue of slavery and, thus, failed to forge a real nation out of the separately sovereign states. The truth is that the Constitution was agnostic on the issue of slavery. True, as Sean Wilentz has argued, the Constitution, by “refusing to acknowledge the legitimacy of slavery”—or, as the phrase went, “property in man”—“excluded slavery from national law.” Such exclusion is preferable to enshrinement, but it is damning to the argument that the Constitution forged a nation. If a people cannot agree on the question of slavery—perhaps the most fundamental question of humanity and its dignity—then they do not constitute a single political society. The Constitution may have made the “Union” of the states “more perfect,” but it would be up to the Civil War to transform that Union into a nation.

The North’s victory in the Civil War and the ratification of the Reconstruction Amendments marked, in the words of historian James McPherson, a “transition of the United States to a singular noun. The ‘Union’ also became the nation.” Lincoln’s own rhetoric over the course of the war changed from odes to “Union” to celebrations of the American “nation” as the war neared its end. The amendments made possible by the war, because of the blood spilled during its course, forcibly forged consensus where it was needed. The most basic embodiment of the Declaration’s principles, the right not to be owned by another person, was finally given uniform, national, constitutional protection.

While Lincoln saw the war as giving the American nation “a new birth of freedom,” that freedom was the very means by which the American nation itself finally came to fruition. With slavery abolished and the constitutional machinery to protect Americans’ most fundamental human rights put into place, an American nation could actually be formed in the minds, hearts, and laws of Americans. This would take time and is still taking time. But the Civil War resolved the question of American nationhood once and for all.

There is indeed an “electric cord” linking contemporary Americans to past Americans, as Lincoln claimed; but that cord links us not to the slave masters of 1619 or the statesmen of 1776, but to Lincoln himself, and to Frederick Douglass and the rest of the Civil War generation that finally forged an American nation. Despite what the 1619 Project claims, we do not live in Stephen Douglas’ America, founded “on the white basis;” nor do we live in Washington’s, Madison’s, or Jefferson’s America, a fundamentally contested Union of separate states.

The key political question today is that of which conflicts must be settled nationally and which can be left to sub-national forums. Once more, the Civil War Founding—the 1865 Project—provides an answer. In 1858 Lincoln prophesied, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” Americans could not remain countrymen if they could not agree about a question as fundamental as slavery. Other disagreements—i.e., normal politics—could and should flourish. The task of self-government is to figure out where questions reside on that continuum of gravity.

We should keep William James’ idea of “selective attention” in mind as we write and pass down our history. Much of the job of telling a national story consists of deciding where to focus. We can focus on the initial, coerced arrivals of servants and slaves to our shores, or the signing of the Declaration of Independence, or the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, or any number of events. Where we place our focus will always be a judgment call. Indeed, why might Lincoln have grounded American nationhood in the Declaration’s ideals of the unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? Perhaps because they so clearly vindicated his resolute anti-slavery stance.

We can take a page out of Lincoln’s book even as we push back a bit on his 1776-centric national story. For our purposes in 2021, we need a national story that better helps us grapple with the puzzle of how to navigate our differences while doubling down on our commitment to the human rights articulated by the Declaration and giving a greater ownership stake in the nation to those Americans who have so often been shunted aside. Neither the pessimism of 1619 nor the optimism of 1776 does that, but the resolution of the conflict of 1865 does.

Grounding the creation of our national self in 1865 will not solve all of our most pressing political questions, but will at least provide a more helpful framework for thinking through them. Which issues of the day warrant—or, rather, demand—uniformity, and which do not? Grappling with this question constitutes America at its best; ignoring it is America at its worst.

Thomas Koenig is a recent graduate of Princeton University. He will enter Harvard Law School in the fall of 2021. Twitter @TomsTakes98

Image: Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1484303

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe