Why Analog is Better than Digital I: The Vinyl Revival

I first became aware of the existence of high-end audio back in the early 1980s Marty Peretz days of The New Republic, when the magazine published an article asking their readers what they thought was the most one could pay for a turntable to play records (this was just before the advent of the Compact Disc). The article’s author then explained that a new Linn Sondek turntable would cost $3,000 and said, “you read that right—the decimal point is not misplaced” (I don’t have the exact quote because the magazine’s digital archives don’t go back that far). It was a revelation to me that such expensive audio components existed, and I soon discovered the huge world of products available to audiophiles, items that were at the time way beyond anything I could aspire to afford.

So what’s the most you think you could pay for a turntable in the year 2021? The most expensive one of which I am aware is a Japanese product called the TechDAS Air Force Zero turntable, which retails for $450,000.

You read that right, the decimal point is not misplaced. This monster, weighing in at 730 pounds not including power supply or air pump, comes without a tone arm or cartridge, which could easily add another $25,000 to the total price. Indeed, you can mount two arms and two cartridges on this turntable, bringing the total cost to well over half a million dollars.

TechDAS is only one of perhaps a dozen companies selling turntables priced at $100,000 and up. There is a proliferation of phono cartridges—the tiny diamond needles that ride in the grooves of records—that retail for over $10,000 each, which will need to be replaced in three or four years when they wear out. You can pay over $10,000 for the cables that will connect your cartridge to its phono preamplifier.

The very existence of products like this is, in the first instance, a sad commentary on the economic inequality that our globalized world has created. They come out of the same world that produces Hermes Birkin handbags in the million dollar range, or an $18.7 million Bugatti La Voiture Noire. And of course there is the billion dollar palace that, according to Alexei Navalny, Vladimir Putin is building for himself on the Black Sea coast. In these days of pandemic-induced unemployment and spreading misery in developing countries, there is indeed something very indecent about the willingness of the world’s wealthy to drop sums of money like this on items that are so trivial in the larger scheme of things.

OK, but back to the subject of this post: why would anyone want to pay that much for a record-playing turntable? Digital music has conquered the world, streamed directly and in infinite variety right to your smartphone. The digital revolution began thee and a half decades ago with the Compact Disc, which promised “perfect sound forever,” didn’t it?

The problem was that a clean, well-recorded vinyl playing on that Linn Sondek or any other high-end turntable simply sounded better—more alive and realistic—than the same material reproduced digitally. The background noise that many people associated with records—the slight whoosh when the needle settles into the groove—is more a byproduct of a cheap turntable than an inherent quality of records. Audiophiles began to notice that music quality dropped substantially when CDs were introduced. And though the quality of digital recordings and playback has greatly improved over the years, it still does not, in the eyes of many, match the quality of analog reproduction.

There is a technical consideration lying behind this subjective observation. With a vinyl record, you never leave the analog domain. An analog sound wave is converted into analog tracks on the record, which is converted into an analog electrical signal by the cartridge and then amplified and replayed though speakers that reproduce the original analog sound wave in your room. You can preserve much of the original sound by reducing the information loss and distortion at each step of this process.

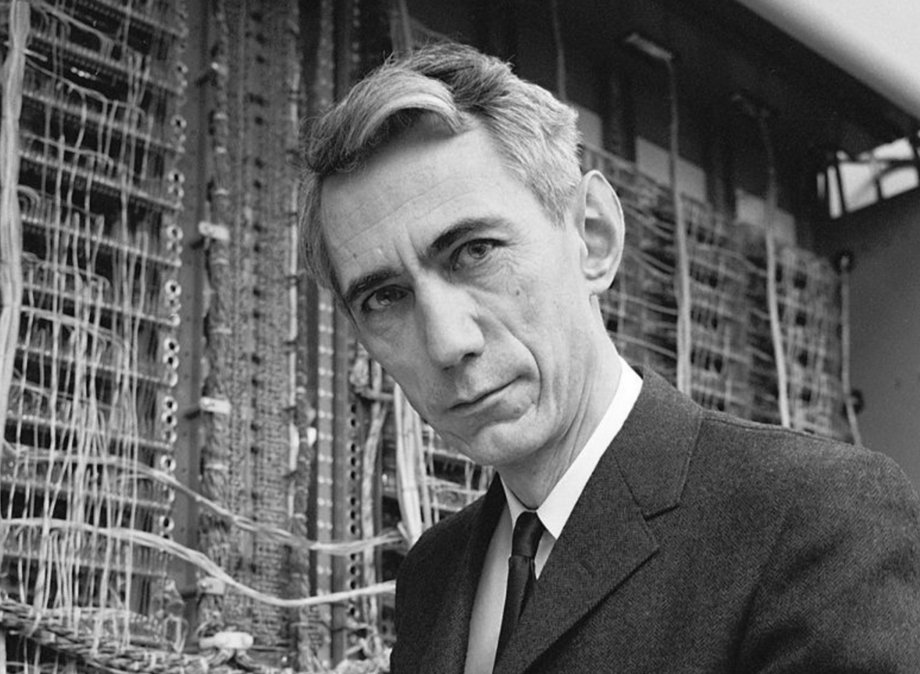

A digital recording interrupts this chain by converting the analog signal into a string of digital ones and zeros. The Shannon-Nyquist theorem, published first in the 1940s, was one of the foundational discoveries that made modern telecommunications possible.

The theorem held that you could accurately reproduce any complex analog wave form by sampling the wave at a frequency that was roughly twice the highest frequency of useful information contained in that wave. The original Redbook CD specification called for a 44.1 kilohertz sample rate with 16 bit words, because it was assumed that no human being could hear sounds above 22,000 hertz. (In actuality, almost none of us can hear signals much above 10,000 hertz).

The problem with the original Redbook format that sound engineers did not at first recognize was that analog-to-digital conversion would leave sonic residues at frequencies well above 22,000 hertz. They were not directly audible but contributed to the thinness or harshness that audiophiles claimed to hear. These residues could in theory be blocked by a “brick wall” low-pass filter, but the latter were hard to implement. There were also timing problems with the digital signal known as jitter, and other issues in implementing the digital-to-analog conversion process like the Ladder DACS that were in use back then. The popular MP3 format is even worse; it saves on disk space by compressing Redbook files using a lossy form of compression.

Over time, these problems in the digital domain have largely been fixed. Today you can download hi-resolution audio files with 24 bit word lengths and sampling rates of 92, 194, and 384 kHz, or the Sony DSD format that uses one-bit words and sample rates in the gigahertz range.

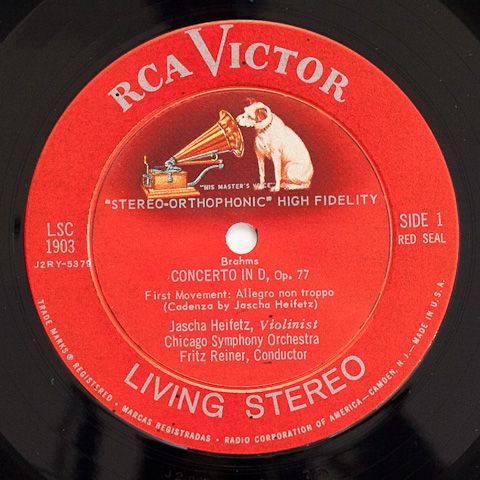

Despite these improvements, the vinyl revival has been going gangbusters. According to the Recording Industry Association of America, more vinyl records were sold than CDs last year for the first time since the 1980s. There has been a huge explosion of new analog product offerings, not just in the $100,000+ range, but at all price points. This has been great news for audiophiles. The best-sounding records were put out in the 1950s and 60s by labels like Mercury Living Presence and RCA Victor (those with “Shaded Dog” logos are particularly prized).

Almost all of those catalogs have been reissued in pristine 180 or 200 gram pressings, from companies that have literally pulled old vinyl-manufacturing equipment out of waste dumps and reconditioned them.

This shift back to vinyl is now less of a search for perfect sound quality as a nostalgic act of tech recovery, similar to the programmers who continue to use old-fashioned text editors noted in an earlier post. There is something very satisfying about the ritual of taking a record out of its sleeve, cleaning it, and putting it on the platter. It is also a way of connecting with earlier times. I have records in my collection that were given to me as birthday presents when I was in elementary school, that sound spectacular when played on a good turntable and cartridge.

A lot of the technological change being hyped as revolutionary is just marketing hype; some of it actually makes our lives worse like the rise of social media at present. The digitization of everything opens us up to vulnerabilities that didn't exist in the analog world, making possible today's pervasive surveillance of everything we do. And it has also lowered the quality of recorded sound.

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe