Material Objects and Virtual Objects

In my recent post describing my long-term hobby of making furniture, I noted that woodworking was broadly speaking a pretty low-tech activity in which nostalgia for old technology played an important role. While this is largely true, that doesn’t mean that it can’t be linked to the virtual world and benefit greatly from some of the tools that the latter provides.

Perhaps the most ambitious woodworking project I ever undertook began when a walnut tree growing in our back yard in McLean, Virginia fell over in a rainstorm. The tree was perhaps 10-12 inches in diameter, and I undertook to harvest its wood. This required using something called an Alaskan Chainsaw Mill, which was a device that held a large chainsaw and allowed you to cut a log down its length into boards. I normally love using chainsaws, but this was a really awful activity—you had to stand behind a really big and noisy 2 cycle chainsaw spewing exhaust for prolonged periods. I cut the tree into 3 inch slabs, then put them into stickered flitches underneath the deck of our house to dry. They stayed there for over a year, and then I brought them indoors to dry further for another year. At that point, I could cut them on my bandsaw into one inch thick boards.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

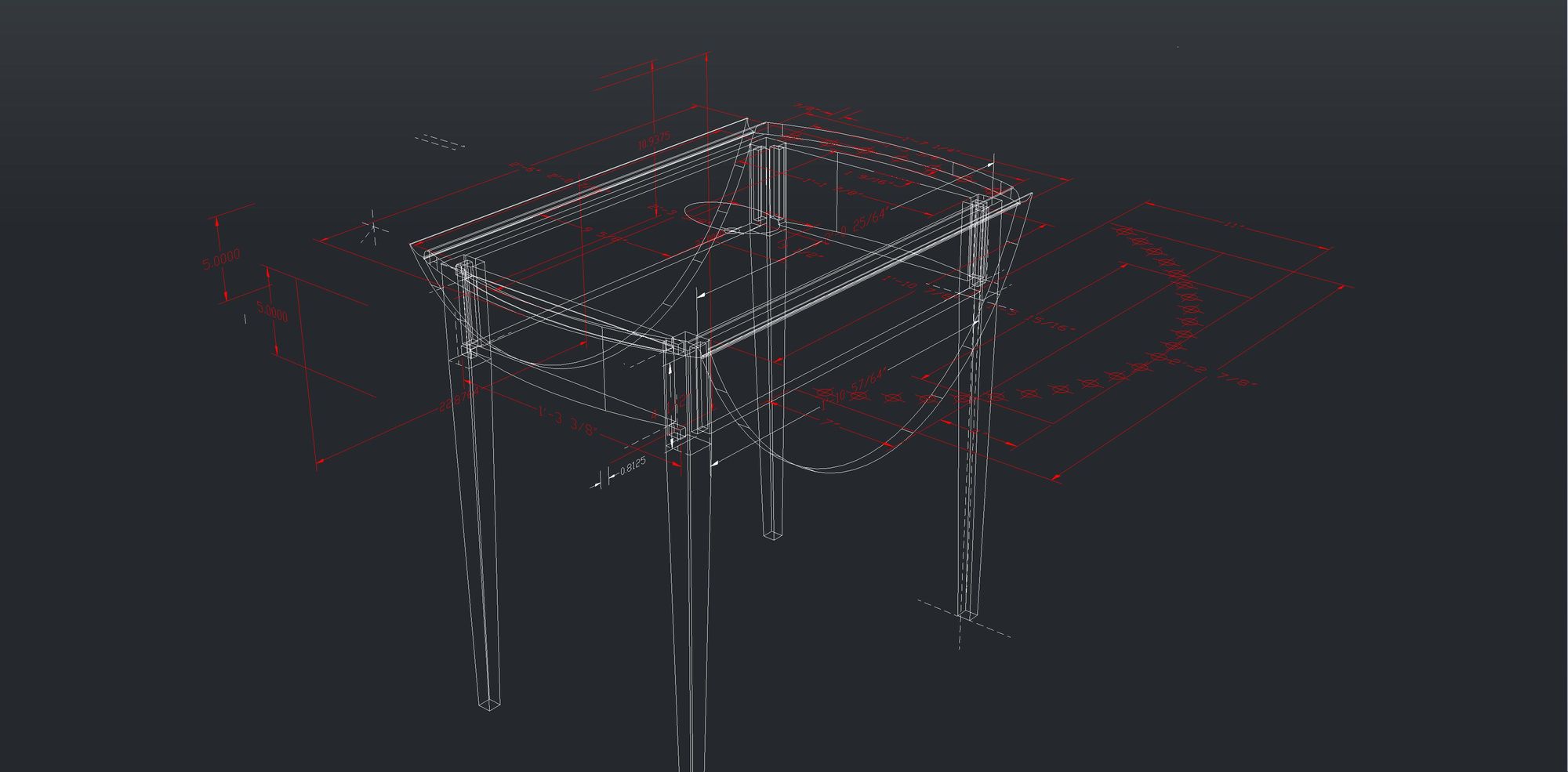

I used the walnut to build a pair of Federal-style Pembroke tables. This is the point at which digital technology entered. I had started using Autodesk’s veteran AutoCAD program to create the plans for the tables. This involved no creativity whatsoever on my part—the design of a Federal Pembroke table has been set for more than 200 years, so it was just a question of learning how to create a 3D model of it.

The great thing about 3D modeling is that once you create the model, you can then place it in a virtual environment to see how it will look. You can build a virtual room, place virtual light sources (including the sun, which will shine in through the room’s windows), and look at your object from a variety of perspectives. When you start this process, you tend to get rather flat and harsh lighting effects.

However, back in the late 1990s when I was learning these programs, I discovered a terrific software package called Lightscape that created highly realistic renderings of virtual spaces. In the real world, light from multiple sources bounces off of wall, floors, and the object itself, and comes in from various directions other than the light source. This tended to soften and warm the way objects were lit. Lightscape replicated this process, lighting the object in a far more realistic manner.

I did, by the way, actually complete the building the two walnut Pembroke tables, seen at the top of this post. They were finished in French polish, inlaid, and sit today in my living room.

The final stage in this process was to move from 3D modeling to animation. I spent countless hours back then building several different houses in AutoCAD in which to place my furniture. One was a Georgian McMansion of which there were many in the new subdivisions in McLean.

The other was a Federal-style townhouse of the sort you might have encountered in downtown Alexandria.

These models were then imported into another complex AutoDesk program called 3D Studio Max (now just 3ds Max), that permitted much more complex renderings. I could then put the 3D furniture models in different rooms, and, in the case of the townhouse, animate a walk-through of the house’s outside and inside. You can see my Pembroke tables against the outside wall in both of these videos.

Rendering an animation is a highly computer-intensive operation; the studios like Pixar that do this for Hollywood movies employ banks of extremely powerful computers organized in render farms that take hours to render just a few seconds of film footage. From my standpoint this was great; it gave me an excuse to build myself an extremely powerful new computer.

After completion of the Pembroke tables, I closed down my woodworking shop entirely. The project took five years from the moment the walnut tree fell to the completion of the two tables, and I was exhausted by the effort. My kids wanted to reclaim the basement so I sold all my power tools and moved on to other activities. I didn’t get restarted in furniture-building until we moved to California and bought a house in Carmel-by-the-Sea. Our little house had a one-car garage that wasn’t really big enough to hold a car, so I turned it into a wood shop, and had an excuse to buy all new power tools. Last year’s pandemic was also a good excuse to build a new, more powerful computer. My current PC has a 12-core Ryzen processer and a very powerful Nvidia graphics card; I re-rendered my old 3DS animations into the higher-res versions that you see in these YouTube posts.

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe