California Dreaming

So Gavin Newsom, governor of California, has survived the recall attempt this past Tuesday by a very substantial margin, and can return to worrying about issues like wildfires, drought, insufficient housing, high cost of living, and the like.

The recall provisions in California’s state constitution, along with ballot initiatives and referenda, are part of a series of provisions put in place in the 1910s by Progressive Era reformers like Governor Hiram Johnson. Together with later legislation like the 1970 California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), they turned the state into what I have labeled a “vetocracy,” where far too many stakeholders have the ability to block collective action and make it impossible to meet the huge governance challenges the state faces, today and in the future.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

While Newsom received some 66 percent of votes against the recall, the pre-election threat of his losing underlined how ridiculous the provision is. The ballot that every California voter received had two parts: in the first, you voted yes or no on the recall, and in the second, you could vote for an alternative candidate. Prior to the election, many observers pointed out that Newsom could lose the recall by 49 percent, and be replaced by a Republican contender like conservative talk show host Larry Elder, who never got more than 30 percent approval statewide. In ballot initiatives, a bare majority of voters can pass a provision that requires a large supermajority of the legislature to repeal. What these provisions do is empower determined minorities to impose their views on majorities. It explains why California Republicans are dead set against changing the recall provisions: since they have not won a statewide office in years in regular elections, a recall is their only chance for gaining power.

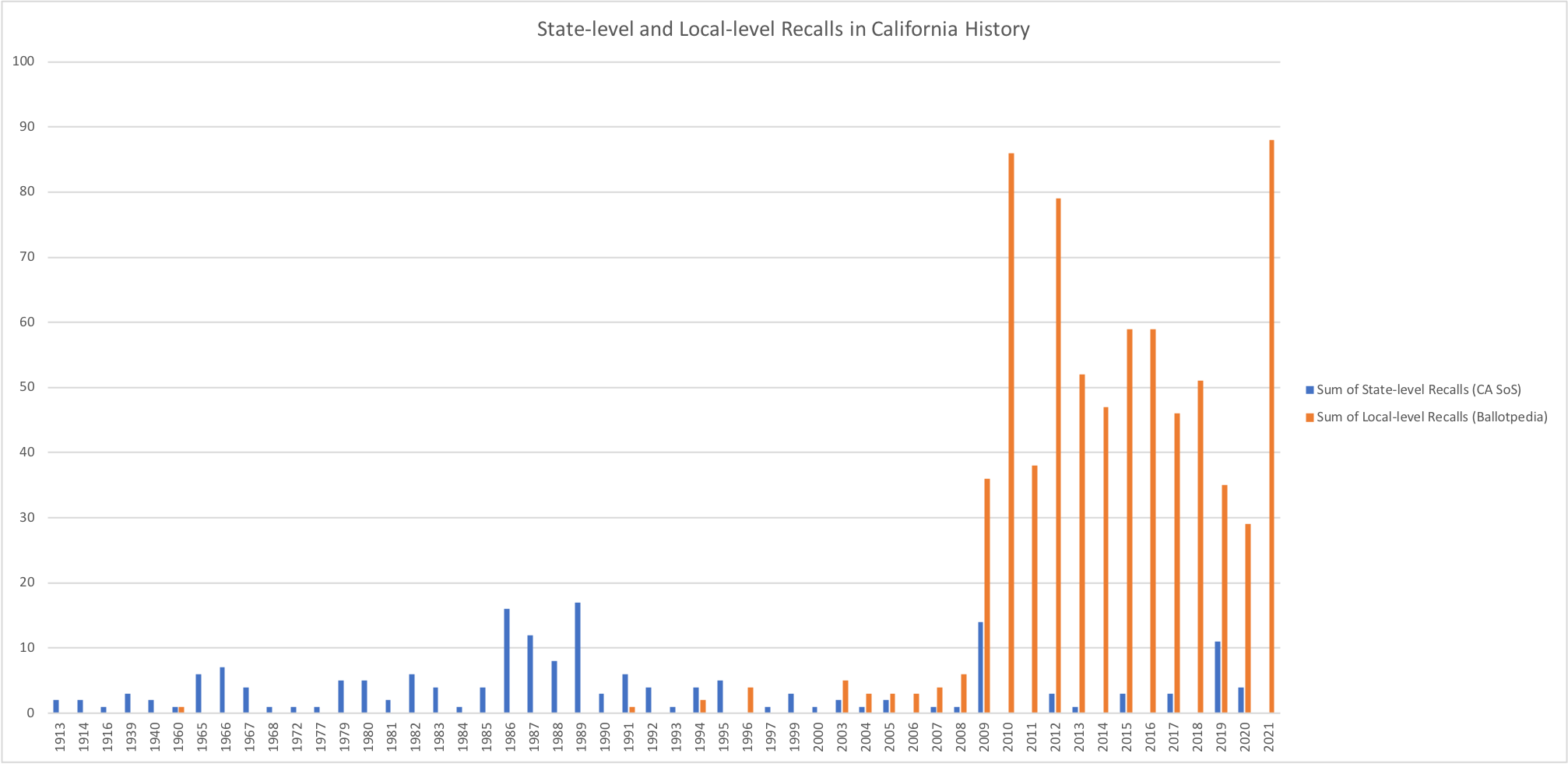

The number of recall efforts, which can take place both at a statewide and local level, has been spiking up in recent years. They are relatively easy to launch, the state-level ones require signatures from 12 percent of the voters in the last gubernatorial election. Up through the early 2000s, there were seldom more than 3 or 4 a year, but after 2009, they have exploded with 88 being filed so far just in 2021.

Almost every Governor has faced a recall effort, and one—Gray Davis—was successfully ousted from office in 2003 and replaced by Arnold Schwarzenegger (who at least won a higher percentage of the vote than Davis). The threat of recalls wastes both time and money, the state having spent some $276 million on election administration and Newsom having raised $70 million to defend himself. But the more important problem is that the constant threat of recalls puts elected officials into a short-term mindset, where they can’t afford to alienate any block of voters who might launch an effort against them.

The initiative process is similarly flawed. Highly complex policies are put before voters in a simplified up-or-down manner. They do not have the opportunity to amend or modify a proposition to make it more palatable or fiscally sustainable. Voters do not have to worry about tradeoffs and contradictions between the present initiative and other laws, and can therefore vote for tax cuts (Proposition 13) or spending increases (Proposition 98 on school funding) without having to worry about its overall effect on the state’s budget. Initiatives and referenda funded by rich individuals often promote particularistic rules, or to block unwanted projects that were meant to serve broad public interest. These direct democracy mechanisms are equally present at the level of local government.

My Stanford colleague Bruce Cain in his book Democracy More or Less has argued that, while the democratic impulse underlying California’s progressive governance institutions is understandable, they embed incorrect behavioral assumptions that have led to unanticipated consequences. Institutions like recalls, referenda, and initiatives assume that ordinary citizens have the time, energy, expertise, and motivation to actively take part in policy decision-making. The fact of the matter is that most citizens do not; the result is that public discussion is dominated by much narrower interest groups that have a direct stake in the outcome of a given policy. Given the size of California, resources also become a major issue; it is hard to launch an initiative or recall without the money to hire a professional organization to gather signatures across the whole state.

Every election, I receive a thick booklet from the state election authorities outlining the different ballot measures that I am asked to vote on. A few years ago there was one asking when actors in the state’s porn industry should be forced to wear condoms while performing. I am a political scientist and deeply concerned with public policy issues, but I never have the time or energy to read through the questions I am asked to decide. Even if I did, I would not be able to make an informed judgment since I don't really know the political forces behind each measure. The people who do pay attention are those directly affected by a ballot measure, who are not representative of the mass of ordinary voters.

The result is that the direct democracy has become a tool of special interests. Recalls, initiatives, and referenda were originally conceived of as ways of getting around corrupt or captured state legislatures, building on California’s experience with the influence of the Southern Pacific Railway in the early twentieth century. Powerful corporations nonetheless figured out how to use the system for their own purposes, disguising their self-interest in misleading advertising campaigns. There have been ballot measures over the years that have brought about real reform, but they are outweighed by the policy incoherence that they foster.

I haven’t at this point even gotten to the problems caused by CEQA, which has become much more than an environmental law and constitutes a dysfunctional governance system for virtually all significant decisions made in the state. That will be covered in a later post. California dreaming is becoming a reality…

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe