OK Boomer

Can a World War II-era movie about an old crank help with generational riddles today?

I am seventeen years old and already suspect that “OK boomer” will be a permanent part of my generation’s lexicon. It’s the insult that young people, from millennials on down, launch at baby boomers—generally between fifty-five and seventy-five years old—who strike them as overly didactic or reactionary. On TikTok, the king of the Gen Z apps, videos with the “OK boomer” hashtag have been viewed more than three billion times. When a twenty-five-year-old member of the New Zealand Parliament was heckled for being young, she retorted, “OK boomer,” and went right on with her speech. The phrase has popped up in “Jeopardy” questions and dictionary entries. The New York Times has even proclaimed that “OK boomer” signals the “end of friendly generational relations.”

The phrase sure seems to be a roadblock. Young people bitterly resent what they see as the self-importance and irascible traditionalism of baby boomers. The boomers, in turn, see the kids as lazy, tech-addicted, politically naive, and evidence of a lamentable decline from previous generations. And boomers have no qualms about saying so (“When I was your age, I had three jobs . . .”), causing millennial anger to boil over.

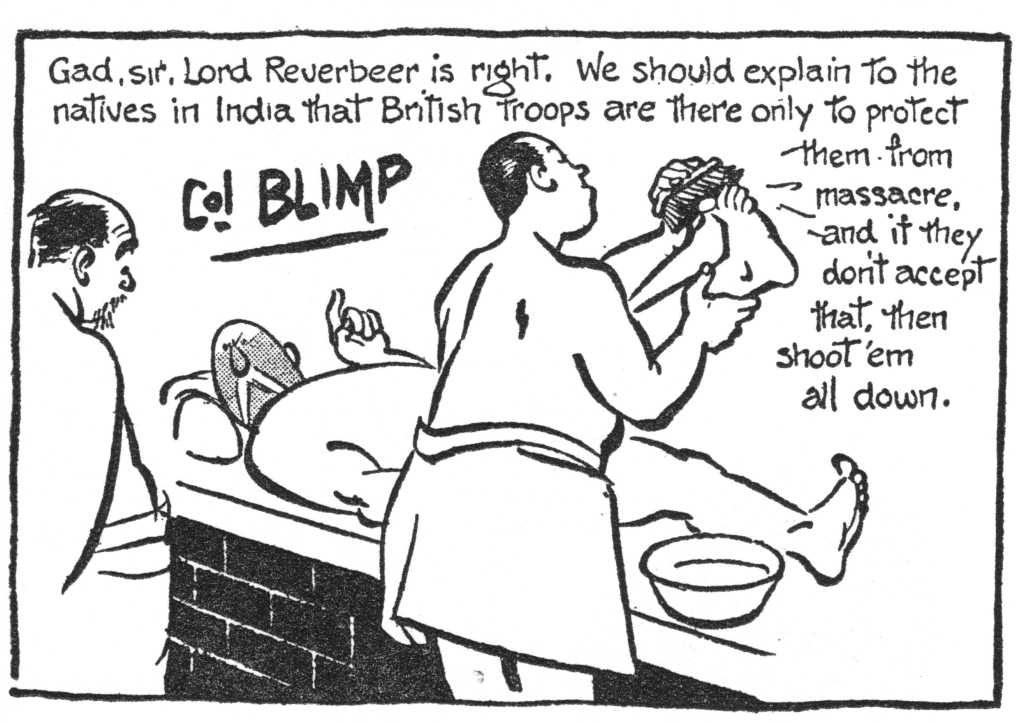

But this is not the first generation to resent perceived pomposity in its elders, and baby boomers aren’t exactly the first to feel that the youth are going down the drain. In 1934, British cartoonist David Low created his own “OK boomer” narrative with a cartoon character he called Colonel Blimp—a stereotypical jingoistic British traditionalist. Having grown up in a milieu of relative power and wealth, and having fought in two successful wars, Blimp treasures the status quo and detests young people who question it. Here is a typical Blimpian tirade:

Colonel Blimp went, as they say, viral. The cartoon was a huge hit when it ran in the London Evening Standard. “Blimp,” meaning pompous reactionary, now appears in the Oxford English Dictionary.

About a decade later, toward the end of World War II, filmmakers Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger produced a movie about the colonel. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was an epic biography of Blimp: his early life, love affairs, friendships, war experiences, and gradual descent into the caricature at which millions of Britons laughed every week. It was as if Martin Scorsese had made a film called The Life and Death of Calvin, in which Calvin, from Bill Waterson’s “Calvin and Hobbes,” is forced in therapy to confront his hallucinations about tigers. The Blimp film turned a conglomeration of mean adjectives (xenophobic, belligerent) into a complex, lovable, even tragic human being. Indeed, such a bold endeavor was not without controversy; though critical reception was generally positive, Prime Minister Winston Churchill hated the film so much that he banned its export.

The Blimp story opens in 1943, as an aged Blimp (for purposes of the film, he’s named General Clive Wynne-Candy) is preparing his Home Guard squad for war with Germany. They have a war exercise scheduled to start at midnight, but some of Blimp’s soldiers decide to ambush him at 6:00 P.M. while he’s resting at the Turkish baths. “We agree to the rules of the game,” says one of the young soldiers, explaining the surprise rule change, but the Germans “keep on kicking us in the pants!”

Blimp sputters with indignation: “You damned bloody idiot—the war starts at midnight!” Blimp is so incensed that he attacks the soldier, toppling them both into the bathwater; here, in physical form, is the battle of young versus old. “You laugh at my big belly,” Blimp shouts at the younger man, “but you don’t know how I got it! You laugh at my mustache, but you don’t know how I grew it!” This is the Colonel Blimp we know and scorn, consumed by disgust at the insolence of the younger generation and unable to recognize the shortcomings of the status quo.

It all feels very familiar. Blimp sounds just like a boomer.

But then comes one of the most magical sequences in all of cinema: As Blimp’s furious, waterlogged cries echo through the bathhouse, we are transported forty years into the past. A slim, dashing, youthful Blimp rises from the water, immediately annoying the old men around him with his strident singing voice. Blimp was young once! The boomers were rebels themselves; the young-versus-old divide is perennial.

We see the life of young Blimp play out. He falls in love with a woman named Edith, played by Deborah Kerr. He fights in the Boer War. He meets a German officer named Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff. The two have a duel (Blimp emerges with a scar on his upper lip, which explains his mustache) before befriending each other. Young Blimp is optimistic, friendly, kind, open-minded—everything, in short, that old Blimp is not.

Getting older, Blimp serves in World War I—and starts to show signs of boomer-ism. In a vain attempt to replicate the past, he marries a woman who looks just like Edith (because like Edith, she’s played by Deborah Kerr). He starts orating. “In this war,” he lectures a younger soldier, “I’ve seen ammunition dumps without ammunition, field kitchens with no cooks, motorcars with no petrol to run on.” By contrast, “In the Boer War, this sort of inefficiency wouldn’t have been tolerated for a second!”

The younger officers, for their part, talk about Blimp behind his back. They say Blimp is out of touch with the modern world; the Boer War was just a “summer maneuver.” OK boomer.

When the British defeat the Germans in the Great War, Blimp celebrates the victory as proof that “clean fighting and honest soldiering have won.” Naturally, when Britain enters World War II, he insists on staying in the military. He is dealt a blow when his superiors axe him from his generalship—because of his age? His increasing pugnaciousness? But Blimp rolls with the punches: He joins the Home Guard and transforms his squad into a proper military unit.

There’s something moving and almost valiant about Blimp’s aggressive resilience: He’s like a young man trapped in an old man’s body (it’s a fitting coincidence that Roger Livesey’s thick old-man makeup and prosthetics barely conceal the actor’s youth). There’s a cruel irony here: It’s the old people who still have attributes of youth, it seems, who clash most violently with the actual young. Contrast this with Blimp’s old war friend, Theo, whose experiences have deflated him into a weary, mild-mannered bystander—i.e., a quintessential “wise old man.” I think my generation has no problem with this kind of elderly figure, but at the same time, Theo’s is an existentially terrifying fate; he has lost the ability to truly feel. For all of Blimp’s officiousness and condescension, at least he hasn’t submitted to that quiet death of the soul.

By the time we meet the final incarnation of Blimp, he has evolved into the cartoon character, but we understand that his pomposity reflects deep unease. He is essentially “out of time;” his fierce defiance is a coping mechanism. At one point he explodes at a young man, “Don’t talk to me about war! I was a soldier when you were a baby, and before you were born … when you were nothing but a toss-up between a girl’s and a boy’s name. I was a soldier then!”

Then, Blimp hangs his head and says quietly, “I’m deeply sorry . . . I know it’s not you.” The empathy and tolerance that characterized his youth emerge despite the belligerence that age has provoked. We understand why Blimp is so enraged by the young soldier who ambushed him at the Turkish bath: this is the last straw, the sign that the world has finally fallen apart completely. To Blimp, young people might as well be aliens.

In its final scene, the film offers a glimpse of hope. Blimp gazes at the shore of a lake where his house used to sit before it was destroyed in the Blitz. “When I was a young chap,” he muses, “I was all gas and gators with no experience worth a damn.” It comes to him that the young soldier in the Turkish bath wasn’t trying to be disrespectful. Blimp decides to invite him over for dinner, as a peace offering—an uncharacteristic beau geste.

Over its course, the film shows how a boomer becomes a boomer, what’s admirable and what’s contemptible in being one, and why boomers provoke the ire of the younger generation. It’s kaleidoscopically empathetic, placing blame at the feet of both old and young. Both are struggling, albeit understandably, to adapt to the strange quandary in which they find themselves.

The upbeat ending can’t, of course, fully solve the problem that the film has exposed—one kind gesture won’t rid the world of intergenerational hostility. Viewed charitably, the directors were trying to rouse feelings of camaraderie and patriotism at a time when Britain needed both. More cynically, one could say that they chose to paper over the darkness of their own film.

Still, Blimp isn’t so much trying to solve the generational riddle as to lay it bare. The problem runs much deeper than one snarky aphorism; “OK boomer” is just a symptom of the disease that the film diagnoses. But we need a diagnosis before we can prescribe a proper cure.

Abe Callard is a Chicago-based writer and filmmaker.

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe