Dressing for Dinner

We can’t reclaim our place at the head of the table if we’re dragging our grandfathers’ State Department behind us. The first in a series of three articles from the author’s forthcoming book.

Overnight, President Biden’s first day on the job in January will generate enormous joy, positive anticipation, and relief for American allies and everyone around the world who values democracy. In contrast with President Trump, Biden has a long track record of embracing democratic allies, especially in Europe, and a demonstrated commitment to advancing democracy and human rights abroad.

I witnessed these qualities personally while traveling with then-Vice President Biden to Georgia and Ukraine in 2009 and to Russia and Moldova in 2011, when Biden chose to meet with both heads of state and human rights activists at every stop. Biden’s return to the White House will also immediately signal America’s active engagement with the world—including re-entry into many international agreements and organizations from which Trump withdrew. As the mayor of Paris tweeted after Biden was declared the winner of the 2020 presidential election, “America Is Back.”

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Showing up again is the first step: Reversing negative trajectories regarding American leadership will be a tremendous accomplishment. Still, it will not be enough. In the time since Biden last served in government, the world has changed. His administration, in turn, will not only have to recalibrate polices but also implement internal reforms of the institutions responsible for the way we interact with the outside world, so that those institutions can successfully address new challenges.

Most important, many national security specialists—Democrats and Republicans alike—now argue that the world has entered a new era of great power politics. For the last twenty years, since September 11, 2001, American strategists have focused on the fight against global terrorism. But the global ideological struggle between democracy and dictatorship—fueled in particular by China’s rise, Russia’s resurgence, Iran’s resilience, and growing autocratic rule and power in other parts of the world—will rightly, if tragically, consume greater attention from U.S. policymakers for decades to come.

The rise of China and Russia is particularly challenging for U.S. national interests. Not only have both countries become increasingly autocratic and powerful internally, but they have in parallel pursued foreign policies that have weakened democratic norms and institutions and strengthened autocratic regimes and illiberal ideologues. As Robert Kagan has argued, “Today, authoritarianism has emerged as the greatest challenge facing the liberal democratic world—a profound ideological, as well as strategic, challenge.”

The rise of these illiberal powers is occurring at a time when international democratic unity and power are waning. The 2020 Munich Security Conference report provocatively called the moment “Westlessness.” In response to these trends, many Americans—government officials as well as analysts, Democrats as well as Republicans—have identified the return of great power competition as the central feature in international politics, and, therefore, the central challenge to U.S. security in the 21st century. Russia and China never left the international stage, but their relative power today has grown from that of a few decades ago or even four years ago. As explained by Richard Fontaine, CEO of the Center for a New American Security and former foreign policy adviser to Senator John McCain, Washington “is settling on a rare bipartisan consensus: the world has entered a new era of great-power competition…. The struggle between the United States and other great powers … will fundamentally shape geopolitics going forward [and] more than terrorism, climate change, or nuclear weapons in Iran or North Korea, the threats posed by these other great powers—namely, China and Russia—will consume U.S. foreign-policy makers in the decades ahead.

Now That We Agree…

Yet, if many national security analysts share this diagnosis, prescriptive new policies from Washington for how to compete in the new era have been fewer and less unified. Everyone agrees that the paramount priority for combating autocracy abroad is to strengthen democracy at home. That sizeable agenda rightly should consume the majority of time and attention of the Biden Administration and their supporters in Congress. (Strengthening American democracy should be a nonpartisan issue.) Through executive orders, the Biden Administration can begin the process of democratic renewal immediately. Many also agree on the need to marshal greater resources for deterring China and Russia—more ships in Asia, more tanks in Europe, less Huawei in 5G networks, and sustaining sanctions on Russian officials responsible for invading Ukraine. What is missing from a strategy for containing (and at times engaging) China, Russia, and other autocracies is a set of new ideas to advance a positive agenda: strategies for relaunching America’s engagement, image, and global support for democratic values.

During the presidential campaign, candidate Biden proposed the idea of a democratic summit early in his administration—an excellent action-forcing event to put on the calendar. Cooperation among democrats and democracies is an essential step. But an international summit without domestic deliverables— internal changes in the way the United States itself sustains and advances democratic ideas—will feel hollow. To demonstrate credible commitment to a grand strategy of supporting democracy worldwide, the Biden Administration must initiate domestic reforms in three fields: diplomacy; public affairs; and democracy and development assistance. In addition to hard power and coercive policies, American leaders must develop better means of globally advancing a positive agenda for democratic ideas and American “soft power,” in Joseph Nye’s term. Returning to the status quo ante, before Trump, is not enough.

During the Cold War, American investments in these latter categories paid off. By the 1990s, no other country could boast a diplomatic footprint or global reputation like ours. When a crisis occurred—be it a civil war or a natural disaster—Washington was the first call, well before Moscow, Beijing, or Brussels. More governments and citizens embraced the ideas of democracy and free markets than perhaps at any other time in history. Hegemonic power was central in advancing these ideas, but public diplomacy, information programs, and development and democratic assistance also played an influential role.

Thirty years later, American diplomacy has atrophied, public communications have become antiquated, and democracy promotion has produced fewer measurable results, as evidenced by fourteen consecutive years of global democratic recession. In 2001, our diplomacy, public affairs, and assistance rightfully refocused on the Middle East, combating violent extremism, and nation-building. The organization chart at the State Department still reflects this shift. But today’s greatest national security challenges stem from the rise of autocratic great powers. Our current doctrines, resources, and bureaucratic organization do not reflect this new reality.

In addition, Trump’s indifference to diplomacy, public engagement, and democracy-promotion dramatically accelerated our decline as the leader of the free world. Withdrawal from international treaties and organizations, alienation of democratic allies, and an embrace of autocratic foes also greatly damaged the reputation of the United States around the world.

To make our diplomacy, strategic communications, and democracy support more effective will require a fundamental rethinking of our strategies and a dramatic reorganization of government structures similar in scale and scope to changes made after 1945, the last time we adopted transformational changes to compete with a rising hostile ideological superpower.

This is the first of a series of three articles in which I outline several concrete ideas for improving diplomacy, information and disinformation operations, and support for democratic ideas. Some of these ideas can be pursued on the first day of a new Biden Administration ; others will take years to implement, requiring new legislation, resources, and ways of thinking. But if this reform agenda will be a long road, why not take the first steps now? The remainder of this essay focuses on enhancing diplomacy. The second article in the series will be devoted to improving public diplomacy, strategic communications, and U.S. government-funded media. The third article will address ways to better support the spread of democratic ideas and democratic institutions, as well as advance sustainable development around the world.

Righting the Ship

A strategy for American diplomatic renewal must start with greater resources for and deeper attention to the State Department. Diplomacy is our first line of defense. As Secretary of Defense James Mattis quipped, “If you don’t fund the State Department fully, then I need to buy more ammunition.” Even with autocratic foes, effective and aggressive diplomacy is needed to reduce misperceptions.

Successful diplomacy requires that diplomats be equipped with sufficient resources, as well as the skills to perform effectively. Current trends are alarming. Too many talented career ambassadors leave public service prematurely. The number of students taking the Foreign Service Officer (FSO) entrance exam has plummeted, although the acceptance rates remain stable. Only 78% of key State Department positions were filled as of November 23, 2020. In 2019, China edged past the United States in the size of its diplomatic network, with 276 posts (i.e., consulates, embassies, and permanent missions to international organizations) to the American network of 275.

The Trump era proved especially demoralizing for career diplomats. As Ambassadors William Burns and Linda Thomas-Greenfield have written about the Trump tenure, “The wreckage at the State Department runs deep. Career diplomats have been systematically sidelined and excluded from senior Washington jobs on an unprecedented scale. The picture overseas is just as grim, with the record quantity of political appointees serving as ambassadors matched by their often dismal quality.” Attacks on the so-called “deep state,” particularly during the Trump impeachment proceedings, were especially damaging.

Yet, the pivot away from diplomacy started as far back as thirty years ago. According to Ambassador William Burns, “Budgets dropped precipitously after the Cold War, with a 50 percent cut in real terms for the State Department and foreign affairs budget between 1985 and 2000.”

These trends must be reversed, first and foremost by hiring more diplomats and devoting greater resources to strengthening diplomatic capabilities. A very detailed and well-researched study, U.S. Diplomatic Service for the 21stCentury, by Ambassadors Nicholas Burns, Marc Grossman, and Marcie Reis, recommends “funding for a 15 percent increase in Foreign Service personnel levels to create a training float like that maintained by the U.S. military.” They further recommend “an increase of 2,000 positions over three years to meet this goal…. After the 15 percent increase in positions is achieved, launch a four-year commitment to increase the size of the Foreign Service by another 1,400–1,800 positions to fill current and projected staffing gaps.” In short, the moment for fundamentally rejuvenating diplomacy is now.

In addition to more diplomats and resources for diplomacy, the balance of power within the U.S. government for national security decision-making must shift toward State and away from the Pentagon. The military’s mission creep expanded during two decades of war in Iraq and Afghanistan, when generals and combatant commanders eclipsed ambassadors and assistant secretaries of state in stature. As Burns writes, “The militarization of diplomacy is a trap, which leads to the overuse—or premature use—of force, and under-emphasis on nonmilitary tools.” Even small changes, such as who attends National Security Council meetings in the White House Situation Room, could amplify the voice of diplomats in national security decision-making. Currently, the Secretary of Defense and the Chairman of the Joints Chiefs of Staff are both members of the National Security Council, outnumbering the sole diplomat, the Secretary of State.

Moreover, we must fundamentally change the way we conduct diplomacy, organize to carry out diplomacy and public affairs, and hire, train, and retain diplomats. In addition to hiring more diplomats and devoting more money to diplomacy, we must attract the best and the brightest. As Uzra Zeya and Jon Finer have written, “The State Department today risks losing the ‘war for talent,’ not only to the private sector but increasingly to other government agencies, due to inflexible career tracks, self-defeating hiring constraints, and a lack of commitment to training and professional development.”

More effective recruitment requires new incentives aligned more closely with 21st-century workforce priorities. One small change would be to make everyone’s first job more attractive. Some diplomats love consular work; many do not. Yet, every new diplomat today, even one with twenty years of experience in a specialized area, is required to immediately do a consular tour. New FSOs should indeed complete a year of service working in consular affairs (American Citizen Services) assisting Americans abroad and processing visas. Engaging directly with people allows FSOs to learn about a new country and culture, and helping Americans abroad is a vital mission of every embassy. However, the State Department should require all new diplomats to serve in another department of the embassy as well, splitting time between consular and other functions. The State Department also must make it easier for dual career families, for example by expanding its capacity to offer jobs that can be performed remotely.

Investing in People

As the Pentagon does effectively, the State Department must provide more opportunities for mid-career training, including an automatic sabbatical for anyone seeking to complete an advanced degree and, eventually, funding to support such training programs. Currently, the military provides officers with three years of full funding to complete Ph.D.’s. The State Department should do the same. Programs like the Lawrence Eagleburger Fellowship, which allows a limited number of FSOs to do one-year “internships” in private-sector companies, should be expanded to send FSOs to non-profit NGOs and state governments as well.

Critically, the State Department promotion system must treat training and detail assignments outside the department as valuable experience and reward good performance in such assignments. Senator Elizabeth Warren has suggested requiring at least one non-traditional assignment—a graduate degree, external detail, or assignment outside a functional area of specialization—for promotion into the Senior Foreign Service. That’s a good first step. The same goes for rewarding diplomats who serve in functional bureaus like the Bureau of Administration.

In addition to greater numbers and more talent, we need diplomats with deeper expertise in functional fields and a commitment to specialization, be it in Mandarin, Russian, Farsi, climate change, cybersecurity, global health, or disinformation. The idea that diplomats should be generalists is outdated. A newly hired FSO who is already fluent in Mandarin and trained in East Asian Studies should work on China, not Bolivia. True, specialization brings the danger of “clientitis”, but to fight it, diplomats could be rotated within regions or between countries with adversarial relations. Russian speakers could serve in both Russia and Ukraine. Mandarin speakers could serve in both the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan.

The practice of training FSOs in multiple difficult languages must end. Sometimes, diplomats spend two years at the Foreign Service Institute studying a foreign language when there are already speakers of the language within the State Department, or speakers can be recruited independently. It should be an advantage in the hiring process to speak a critical foreign language at the outset—or, likewise, have scientific knowledge about cyber, pandemic, or climate issues. To encourage greater specialization, the rigid requirements that compel diplomats to serve abroad or come home must be relaxed. There has been some progress—the Department of State has made it easier for diplomats to stay longer in Washington—but taking advantage of the eased rules is not career enhancing.

The present hierarchal division between FSOs and civil servants must be eliminated. More ambitiously, the Department should make it easier for both diplomats and non-diplomats to serve and rotate out. The current barriers between the State Department and the outside world are too high. How many careers these days span thirty years at one organization, as they do at State? The more porosity between the State Department and the outside world—business, NGOs, academia—the better.

To better represent the United States abroad, American diplomats must better represent all Americans—ethnically, socio-economically, demographically, and geographically. The strides that State has made in this area are admirable but insufficient. As explained by Richard A. Figueroa, a thirty-year State Department veteran, “Despite a decades-old legal mandate, diversity has simply not been a priority at the State Department.” According to Burns and Thomas-Greenfield, “only four of the 189 U.S. ambassadors abroad are Black—hardly a convincing recruiting pitch for woefully underrepresented communities.” Ambassadors Nick Burns, Grossman, and Reis echo the conclusion: The Foreign Service’s “record on diversity is not acceptable.” Today, they report, “the Senior Foreign Service is comprised of only 4 percent African American Officers, 3.6 percent Asian-American Officers, and 0.2 percent American Indian Officers. Also, 5.3 percent identify as Hispanic and 94.7% identify as not Hispanic.” In the same way, geographical diversity must be given greater attention.

To strengthen American diplomacy, the practice of handing ambassadorships to campaign donors must be sharply reduced. Donors cannot become generals; by the same token, we should not allow them to become ambassadors unless qualified. Doling out these positions to donors also impedes the goal of diversifying ambassadorial ranks. Instead, donors could serve on expanded advisory councils like the Foreign Affairs Policy Board. One can imagine an advisory board for each bureau, as well as boards for departments beyond State.

At the same time, the State Department would benefit from a greater infusion of new expertise at both ambassadorial and lower ranks. The expectation that a minimum number of ambassadorships should be reserved for career diplomats must end. For these important positions, we should simply hire the best people, be they career State Department officials, outside experts, or even some donors. It follows that the informal practice of giving certain embassies to political appointees and others to career ambassadors must stop. Even the two labels—career versus political—should be retired: The phrase “political ambassador” suggests that former ambassadors like Ivo Daalder, Michelle Gavin, Doug Lute, Carlos Pascual, Samantha Power, Susan Rice, Dan Shapiro, or Bill Taylor did not have distinguished foreign policy credentials before they were appointed as ambassadors.

The same should be true at lower ranks. For instance, private-sector experts in cybersecurity or disinformation could be given opportunities to do one-year tours in embassies. An academic with particular expertise in a country could spend a sabbatical year working in a non-management position, as an advisor, in an embassy section. In general, diplomats should become more connected to the world outside of government and vice versa.

Organization and Structure

The State Department must do better at the job of learning. As things stand now, diplomats move from assignment to assignment every few years without systematically collecting, codifying, and memorializing their successes and failures in a form from which other diplomats can learn. Diplomacy should be treated less like an art and more like a science. Like other social science disciplines and thousands of private-sector companies, the State Department should build evidence-based learning, artificial intelligence and machine learning, and big data analytics into its work.

In a small first step, the Bureau of Intelligence and Research should create a new “Office of Social Science Research.” The Department should write comprehensive case studies of successes and failures in diplomacy and create a more usable internal database for learning and networking. As Bill Burns has written, there ought to be a “new emphasis on tradecraft, rediscovering diplomatic history, sharpening negotiation skills, and making the lessons of negotiations like the Dayton Peace Accords or the Iranian nuclear talks accessible to practitioners.” Academics should play a greater role in providing analysis and assessments, as well as teaching at the Foreign Service Institute. Current Office of the Inspector General reports rightly focus on the processes of diplomacy, but they must be supplemented by analyses of substantive outcomes, preferably conducted by outside experts on the diplomatic relationships being evaluated.

The State Department, in parallel with other departments and agencies devoted to national security, must develop better information flows about expertise—what Anne-Marie Slaughter describes as a “Google for Government”—to match talented individuals more effectively to problems, especially during crises. The State Department must create new mechanisms for assembling and disassembling task forces on immediate problems and questions requiring expert attention. These task forces could be composed of both U.S. government officials and outsiders hired for finite amounts of time. As Burns has noted wryly, “The State Department is rarely accused of being too agile;” we should start changing that opinion.

A rebalancing of diplomatic engagement is needed. The massive embassies in Iraq and Afghanistan must be scaled back, while our diplomatic presence in Russia and China’s regions must be expanded. And those countries sandwiched between China and Russia in Central Asia need an upgrade, while American diplomatic engagement in multilateral institutions must increase dramatically. This is especially true for the regulatory and standard-setting organizations to which the Chinese have devoted their special attention of late.

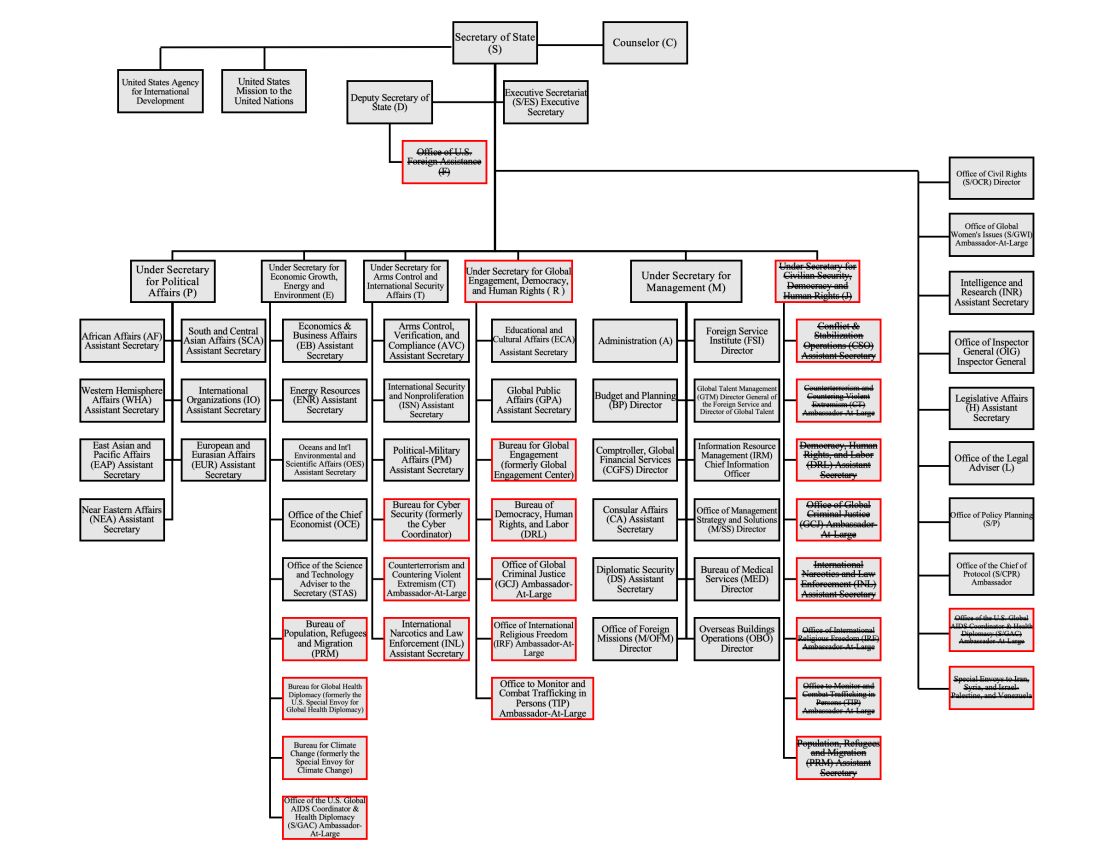

Finally, the State Department organizational chart needs restructuring. Reforms put in place after September 11 to fight terrorism and rebuild war-torn societies are now impediments to addressing the most salient diplomatic challenges of the 2020s. If the greatest diplomatic challenge today is addressing the return of great power competition, and if the greatest existential threat to the United States and the world is climate change, then the Department of State must reorganize and rationalize accordingly.

To provide greater focus on competing with ideologically driven autocracies, the Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs (R) needs to be strengthened. The current Global Engagement Center needs to be upgraded to a new bureau, run by an assistant secretary and radically expanded to be able to expose, deter, and slow the spread of anti-American disinformation. The Global Engagement Center rightly provides funding to external actors but must build greater internal capacity and develop closer partnerships with American social media companies.

The Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL), which now reports to the Under Secretary for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights (J), should instead report to the Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs—so that democracy, human rights, public diplomacy, and strategic communication become more integrated. The lead policymaker should be renamed the Under Secretary for Global Engagement, Democracy, and Human Rights. (Every bureau and every diplomat abroad must practice “public affairs.” Separating this assignment sends the wrong signal.) Other bureaus that currently report to the Under Secretary for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights should move elsewhere. For instance, the Bureau of Counterterrorism should instead report to the Under Secretary of Arms Control and International Security Affairs (T). The Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO), if it is continued, should report to the Under Secretary for Economic Growth, Energy, and the Environment, as should the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration.

The Office of International Health and Biodefense (IHB) should be upgraded to a Bureau, with an assistant secretary, reporting to the Under Secretary for Economic Growth, Energy, and the Environment and taking responsibility for fighting global pandemics. Likewise, the Office of Global Change, formerly the Special Envoy for Climate Change, should have an Assistant Secretary for Sustainable Development and Climate Change and be given new billets and resources to complement and support the work of Biden’s Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, John Kerry. Every embassy should have at least one climate change officer.

To compete with China on trade and investment more effectively and better connect our economic diplomacy to the needs of the American people, the Under Secretary for Economic Growth, Energy, and the Environment also must be strengthened, especially its Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs (EB). The latter must have a greater presence within the State Department headquarters in Washington, a bigger role at every embassy, and work in close cooperation with the Department of Commerce and the International Development Finance Corporation.

As will be discussed in detail in the second article in this series, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) must become more independent from the State Department to deliver more effectively on advancing sustainable development. As such, the position of Director of Foreign Assistance within State is no longer needed. But if the position continues to exist, then the Director of Foreign Assistance should stop reporting directly to the Secretary of State and instead fold into the Under Secretary for Economic Growth, Energy, and the Environment. Future aid provided by the State Department should involve only security, law enforcement, and economic and humanitarian aid to foreign governments. All U.S. aid to foreign non-governmental organizations should be provided by either USAID or American NGOs.

The new State Department organizational chart would create three functional clusters—security, prosperity (including health, climate, and development), and values—that reflect the three top foreign policy priorities of the American people.

To enhance efficiency and rationalization, nearly all of the special advisors who now report directly to the Secretary of State should be folded back into the appropriate bureaus—or eliminated. The cyber coordinator, for instance, should be reclassified as an assistant secretary under the Under Secretary of Arms Control and International Security (T). Special envoys to Iran, Syria, and Israel-Palestine must be folded back into the Bureau of Near East Affairs (NEA) or eliminated. The Venezuelan envoy should be eliminated or returned to the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs (WHA).

Some of the changes recommended in this essay are small, others gigantic. More pressing priorities, like the pandemic and economic recession, along with bureaucratic inertia and political gridlock, will pose resistance to these recommended transformational changes. If, however, the international system moves increasingly toward a global competition between liberalism and illiberalism, democracy versus autocracy, and great power rivalry, then the United Stated cannot succeed in defending our interests or values through incrementalism. At the advent of the Cold War, American leaders started slowly but eventually implemented fundamental institutional changes in the way our national security apparatus was organized. If we are entering a new era that is similarly challenging in scale and scope to our fundamental national interests, we need a similarly creative reorganization of the way we conduct diplomacy.

Enhancing diplomacy is the first step. Modernizing our public diplomacy, state-run media, and strategic communications is a second step. Rethinking democratic and development support is a third step. Stay tuned for subsequent articles on these additional reforms.

Michael McFaul, a member of the editorial board of American Purpose, is director of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Ken Olivier and Angela Nomellini Professor of International Studies, and Peter and Helen Bing Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, all at Stanford University. He served as senior director for Russian and Eurasian Affairs at the National Security Council and as U.S. ambassador to the Russian Federation in the Obama Administration. This article is the first in a series of three adapted from his forthcoming book, American Renewal: Lessons from the Cold War for Competing with China and Russia Today (2021).

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe