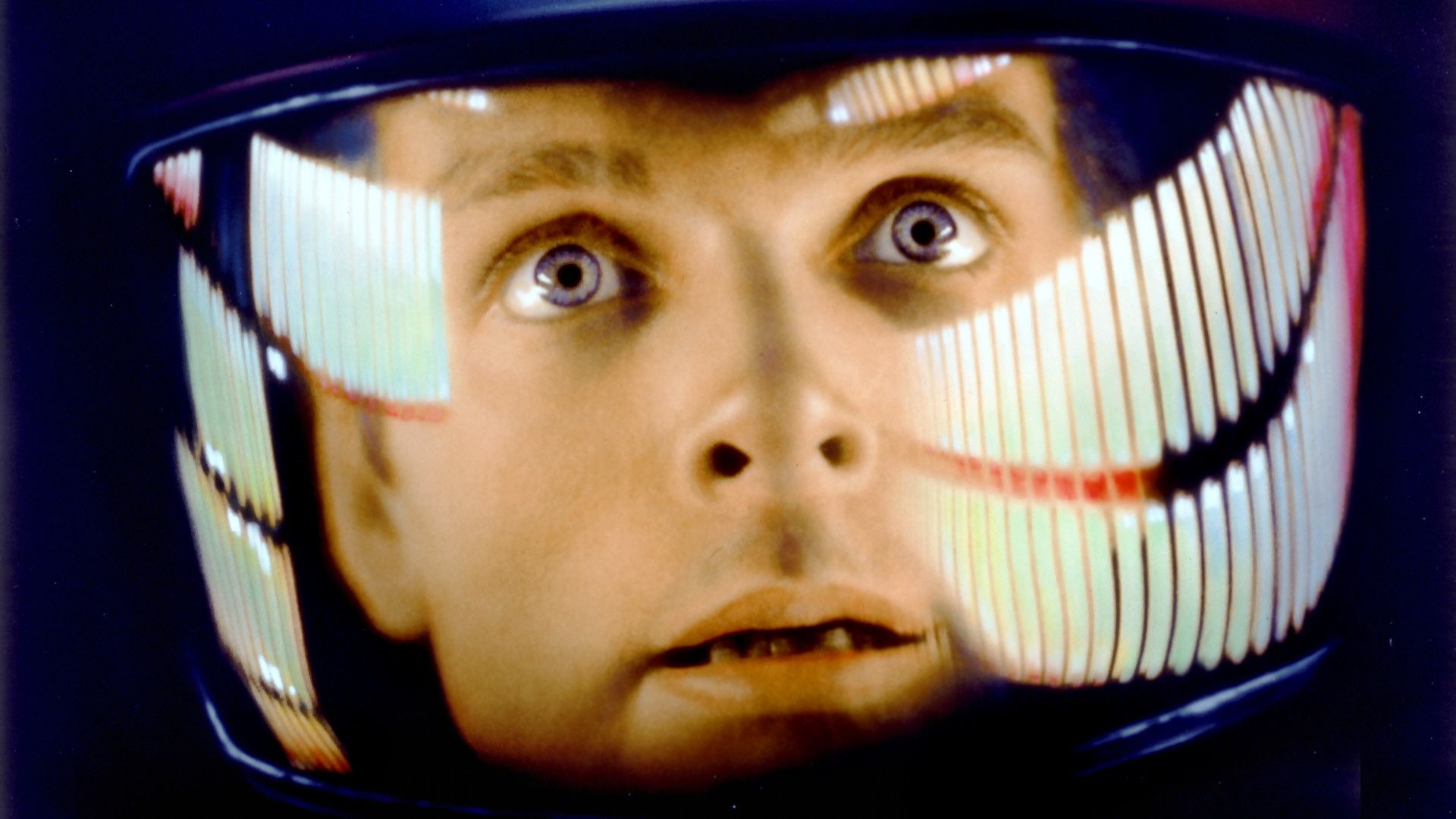

2001: A Space Odyssey

Francis Fukuyama on sci-fi’s shift from techno-optimism to techno-pessimism.

I recently watched Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey which was being streamed on one of the services to which I subscribe. The film first appeared in 1968, when I was sixteen and just entering high school. I watched it then; though it has been discussed endlessly ever since, I hadn’t sat through it again until just recently. I must say, it made me feel really old.

When Kubrick’s film came out, the year 2001 was thirty-three years in the future, which seemed incredibly far away. In those days, science fiction could imagine that space travel would have become routine by that date, with human beings living on the moon and undertaking manned voyages to Jupiter. The actual moon landing would occur the year following the film, which added to the widespread feeling that technology was advancing at a miraculous pace. The prospect of colonizing space opened up a huge frontier of hope and possibility.

Today, it is twenty-two years after the events predicted in the film, which makes me, from the perspective of the year 1968, not just old but a creature of even more distant future.___STEADY_PAYWALL___

While Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek had already premiered on TV in 1966, 2001 was the first high production-value space odyssey. The opening sequence where the camera slowly pans past a huge and fantastically detailed space ship has become a movie cliché, creating a reality far beyond the plastic models hanging from strings that characterized the early Star Trek episodes. 2001 would be followed in 1977 by the Star Wars franchise, and later ones like Universal Studio’s remake of Battlestar Galactica in the early 2000s and the recently concluded Expanse series that was first produced by the SciFi Channel and later picked up by Amazon Prime.

I have to confess that I love space operas, and their premise that humankind is on the cusp of a new period of exploration and possibility. Unfortunately, the year 2001 came and went, and now, twenty-two years later, NASA is just now undertaking a return visit to the moon. There are no warp drives or wormholes that humans can pass through so they can exceed the speed of light; the idea that we will get as far as Mars is still a dream that will take years to realize, if it ever happens. From the perspective of the present, the optimistic hope that technology would allow humans to live on distant planets and visit even more distant galaxies may never materialize.

The one theme in 2001 that now seems to be coming true is artificial intelligence. The HAL 2000 computer that turns against the human crew of the Jupiter mission sounds very much like a vocalized ChatGPT. Of course, we are very far from having anything like generalized artificial intelligence that is capable of acting autonomously in this fashion. But the advent of generative AI has rekindled fears that we are heading in that direction, and some technologists think that, unlike Jupiter, we will actually get there.

Other things that 2001 projected into the future have changed dramatically. The women in 2001 are mostly space stewardesses, dressed in weird hats and serving drinks to the men who run the space station. There is a female member of the international committee running the Jupiter mission, but she speaks with a Russian accent. The movie is filled with product placements for firms that went bankrupt or lost their former glory, like the Howard Johnson’s restaurant aboard the orbiting space station and the IBM computer guiding the spacecraft.

In the years since 2001, science fiction has gotten a lot gloomier.

The genre is largely dominated today by post-apocalyptic futures in which mankind is devastated by plagues, environmental collapse, genetic manipulation, or nuclear war. This of course is the origin of the whole zombie genre, which has gone on so long that it has produced a big sub-genre of zombie movie parodies (e.g., Shaun of the Dead, Zombieland). More high-minded literary examples of the post-apocalyptic genre are Oliva Butler’s Parable of the Sower, Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake trilogy, or The Road by Cormack McCarthy (who just passed away on June 13) that was made into a film. These novels are utterly bleak, in which humans are reduced to isolated individuals battling one another in a Hobbesean war of all against all.

We’ve thus traced an arc in the fifty-five years since the premiere of 2001, from techno-optimism to techno-pessimism. The old space odysseys' routinized complex technologies don’t yet exist, like the Expanse’s Epstein drives or regenerative medicine. They projected many of today’s conflicts and political structures into the future, but in ways that we could assimilate to our normal experience. Star Trek’s Federation was an alliance of liberal democracies battling an authoritarian Klingon Empire that looked much like the old Soviet Union. The Expanse’s fight between the inner planets and the Belters is simply today’s class and race conflicts elevated to the scale of the solar system.

The premise of all post-apocalyptic films and books, by contrast, is that our increasingly complex hi-tech civilization is unsustainable, and that at a certain point it will collapse on itself and return us to an earlier period of human history. We’ve lost the heady faith in technology that existed during the 1960s, and replaced it with a foreboding about the unanticipated negative consequences of virtually any technological advance.

I for one enjoyed the former fantasy more than the one that succeeded it. But I have no idea how realistic either one is. There is a third, perhaps more chilling prospect: that in 100 or 200 years, the world will look essentially the same as it does now, only a bit grungier and with a loss of hope for any significant change in the future.

Francis Fukuyama is chairman of the editorial board of American Purpose and Olivier Nomellini Senior Fellow and director of the Ford Dorsey Master’s in International Policy program at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

Image: Keir Dullea in 2001: A Space Odyssey. (IMBD)

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe