The Good Listener: A Halloween Trick

A cautionary tale about clever Halloween costumes.

My neighbors down the street love Halloween. They go all out, transforming their lawn and front door into a scene of fantastical horror. One year, to my delight, they staged a pair of skeletons rowing a kayak across the lawn. And they throw a big party, which I always try to attend.

The party has one rule: You must come in costume or the host is going to be upset with you. I violated the rule once and the host gave me a very sharp look. I now take dressing for the party more seriously.

At one of these parties a few years ago I learned a lesson about stepping out of yourself to become someone else. In this time of anxiety around in-person socializing, when some of us feel harangued by instructions on how to recognize others’ feelings through our words and what we eat and watch and read, I think the story bears telling.

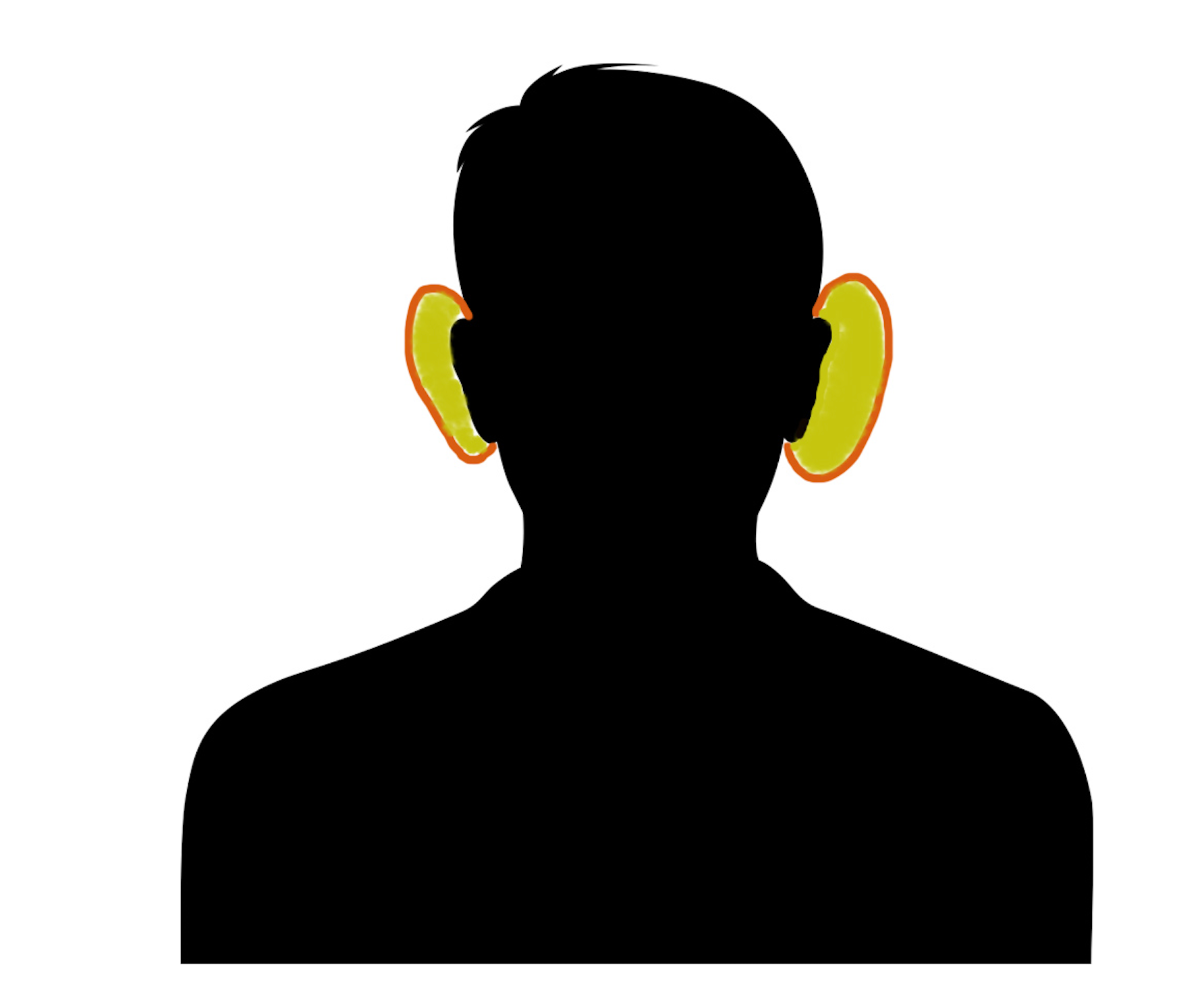

The moment of truth for many costumes comes when people first see you and, because you are not impersonating someone famous like Bart Simpson or Dolly Parton, they have to ask, What are you? On the night in question, I wanted to build my costume around that moment. And I decided my answer would go like this: I would lock eyes with the person asking the question and gently say, “I am a really good listener.”

To add some visuals to this idea I took a padded manilla envelope and cut out pieces shaped like the letter D and slid them over my ears to make my ears extra large, like a hobbit’s ears. And that was it. My costume was complete.

My line, though delivered well enough, had little effect on the first person I encountered, my across-the-street neighbor. He wrinkled his nose and said, “Cute,” but in the most withering way possible. Another person, also a man, seemed totally nonplussed when I delivered my line. He immediately noticed someone he just had to say hi to.

This costume idea was failing hard, I thought. But then a woman whom I had never met before asked what I was supposed to be. I looked her directly in the eyes and said, as planned, “I am a really good listener.”

She looked back at me, laughed nervously, and said, “You are?”

“Yes,” I replied, not blinking.

It was several minutes before she stopped talking. I heard about her last two jobs, some marital difficulty, moving houses, and—because her story came with a complete narrative arc—finally recapturing the joy that had escaped her, lo, these many unhappy years. And my prosthetic ears, like one of those trumpets old people used to hold to their ear canals, were helping me to hear everything she said, even at a crowded party.

I had not given much thought to what would happen after I delivered my line but I tried to play the role I had chosen. When this lovely woman finished her story, I asked a couple of follow-up questions but did not know what to do next. I felt really connected to her, but awkwardly so, for there was no organic context for all that had been said. I felt badly about moving on, but it was a party, after all, so I tore myself away.

Then, no more than a minute later, it happened again. A woman asked me what I was supposed to be. I looked her directly in the eyes and told her. Suddenly, between us, a full-blown mental channel was in place, an understanding that might have taken months to establish otherwise. She told me so much about herself that I felt like her new best friend, her confidante. And, again, I found it difficult to leave.

What came to mind at this point was the moment in crime shows when the undercover cop starts to lose perspective and someone inevitably says, “You’re in too deep. You’re way too close to this.”

I decided to give my “good listener” act a rest and say hello to some male friends. Still, as I made my way to the firepit, the same thing happened a couple more times, always with women. The intensity of these exchanges decreased somewhat, but not a lot, and it may have had more to do with the fact that I was exhausted. I felt like a shrink badly in need of a cigarette break.

Had I stumbled onto some ancient code of the Secret Order of the Pickup Artist? Had I, during the height of #MeToo, discovered a truly humane way of talking with the other half of the species? Had I found the answer to Sigmund Freud’s famous question, What does a women want? I have no idea.

In any case, I am a happily married man and there are rules for socializing with women. It occurred to me that I was probably violating several of them. For one, I was committing the opposite of small talk. Worse, maybe I was trifling with these women’s stories, idly handling serious material. But when I listened, I felt for them. I felt we had a connection. I wanted to know more. Oh yes, the trick had played me. And it was not because of anything I had said. It was because of my willingness to hear these people, to be their audience. Listening—albeit sustained, focused listening—was all it took.

Words matter, people keep saying these days, as if our choice of words were everything and showing respect merely a question of adopting the latest fashions in approved vocabulary. I think words do matter, but so do intentions, so does the overall regard we show other human beings. Respect, consideration—these are powerful, even magical, forces when it comes to crossing the divides that separate us. If you doubt me, I suggest you try it. The next time someone says, “Can I tell you something?,” look them in the eyes and say, “I am all ears.”

David Skinner is an editor and writer. He is author of The Story of Ain’t: America, Its Language, and the Most Controversial Dictionary Ever Published (2012) and many essays on literary culture and history.

Image: A lawn skeleton drowning (presumably) in conversation. (Flickr: Susannah Anderson)

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe