Henry Kissinger at 100

The former secretary of state has had a distinguished public career, one well worth remembering on his one hundredth birthday.

On May 27, Henry Kissinger will reach a personal milestone, his 100th birthday. This actuarial accomplishment provides an occasion to recall and assess his considerable achievements, which make his career one of the most influential and important in the history of American foreign policy.

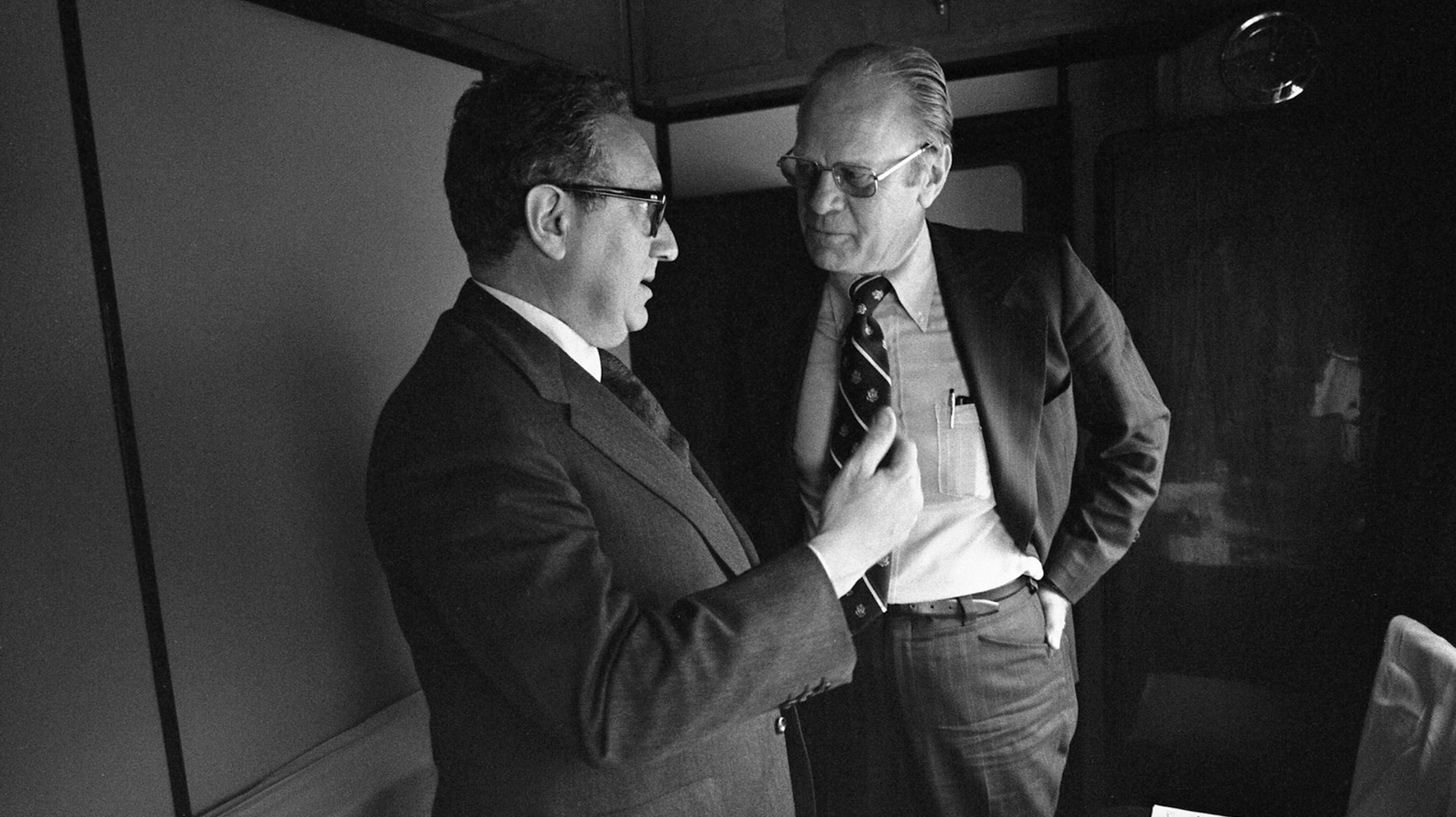

Kissinger served as national security advisor from 1969 to 1973 and as secretary of state from 1973 to 1977, during the presidencies first of Richard Nixon and then, after Nixon resigned in 1974, of Gerald Ford. The Nixon administration took office with American foreign policy under considerable stress. The United States was bogged down in an apparently unwinnable war in Vietnam in which 500,000 American troops were engaged. The conflict was consuming the energy, the attention, and the resources of the American government and creating increasingly acrimonious divisions within the American public. With Kissinger playing a crucial role, the administration launched five major initiatives designed to relieve the mounting foreign and domestic pressures on the United States.

In Vietnam, it carried out a policy of “Vietnamization”–substituting Vietnamese for American ground troops, which, by April 1973, had all departed the country; it undertook negotiations for a political settlement to the war; and it temporarily escalated the military effort on several occasions in order to prevent the collapse of the South Vietnamese government that the United States was supporting.

Toward America’s chief adversary, the Soviet Union, the administration initiated a policy of détente–a French term for the relaxation of tensions. Détente consisted of periodic conferences between the leaders of the two countries that became known as summit meetings, the inauguration of modest economic ties, and negotiations that yielded agreements to place limits on the nuclear weapons the two sides deployed against each other.

To strengthen the American position in Asia, the Nixon administration effected a diplomatic rapprochement with the communist government of mainland China, from which the United States had been estranged since 1949 when the communists had won the Chinese civil war and seized control of the country. To consummate the new relationship, President Nixon made a dramatic trip to China in February 1972. In October of the next year, a war between Israel and its Arab neighbors erupted. The United States brokered a cease-fire and then a series of disengagement agreements, thereby easing the threat to American interests in the Middle East and beyond. Finally, on August 15, 1971, the administration ceased redeeming for gold dollars held by foreign governments, thus ending the international monetary order that had been established at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944. The central role of the United States in that order was imposing increasing costs on the American economy.

Together these measures lowered the cost to the United States of waging the Cold War without abandoning the pursuit of that global conflict. The Nixon administration, that is, executed a midcourse correction in American foreign policy in order to avoid making a U-turn.

Although Henry Kissinger played only a marginal part in the events of August 15, 1971, he was central to the other four initiatives. If Richard Nixon, as president, acted, in effect, as the chief executive officer of American foreign policy during those years, Kissinger became the equivalent of the chief operating officer–and an unusually influential one.

Specifically, he had operational responsibility for conducting the negotiations involved in each of the four initiatives. After multiple meetings he concluded an agreement intended to bring an end the Vietnam War. The agreement did not, as it turned out, actually end the war, but it did help extricate American troops from the conflict, thereby more or less eliminating American casualties. For this work Kissinger and his North Vietnamese opposite number, Le Duc Tho, jointly received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973.

Kissinger negotiated, as well, the various agreements with the Soviet Union that détente entailed, including the final details of the nuclear arms accords. He led the secret talks that paved the way for the rapprochement with the communist Chinese regime and he accompanied President Nixon to China. During their visit, Kissinger hammered out, with Chinese officials, the terms of the Shanghai Communiqué, a joint statement that concerned, among other things, the status of the island of Taiwan off the southeast coast of China. The communist government asserted that Taiwan belonged under its control, while the United States had helped to protect the island’s de facto independence since 1950.

Finally, by shuttling back and forth between and among the capitals of Israel, Egypt, and Syria–the combatants in the 1973 Middle Eastern War–Kissinger, by then secretary of state, secured the military disengagement accords between Israel and its Arab neighbors. These served a number of important American interests: they prevented the resumption of the war, they ended the oil embargo that the Arab oil-exporting states had imposed in connection with the war, and they paved the way for a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt that made another large-scale Arab-Israeli military conflict all but impossible.

The intensity and the scope of these diplomatic undertakings, and their success–in the sense that they all culminated in agreements–has no parallel in American history, and perhaps no parallel in the history of any country. With his prodigies of diplomacy Henry Kissinger made his mark on the twentieth century.

His diplomatic achievements were all the more remarkable because, before his high-level government service, he lacked the kind of background likely to have prepared him for such efforts. He came to office not from the practice of law or from business, where negotiation is common, but rather from the academy, where the skills he employed are generally neither needed nor, as a rule, cultivated. The kind of diplomacy that he practiced came to define the job of the secretary of state. Until well into the twenty-first century, his successors (and other foreign policy officials as well) devoted their time to pursuing the kinds of negotiations, sometimes in secret, in which he had excelled.

During his years in office and thereafter the policies with which Kissinger was associated came in for criticism, some of it heated and bitter–as is normal in democracies. The American policy in Vietnam extended the war, leading to tens of thousands of American and Vietnamese deaths, and ended in failure: communist North Vietnam ultimately conquered and took control of South Vietnam, which the United States had expended considerable blood and treasure in trying to sustain. In retrospect, Nixon’s decision upon entering office not to terminate forthwith the American involvement in the war that he inherited from his Democratic predecessors, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, but rather to draw it out in the hope of securing a non-communist South Vietnam, may seem unwise. Nixon made that decision, with Kissinger’s concurrence, out of a concern that an abrupt withdrawal would lead quickly to a South Vietnamese collapse, which would in turn damage American’s position, and embolden its communist adversaries, both in Asia and elsewhere. With hindsight it can be argued that that concern was misguided, but it was neither irrational nor dishonorable at the time.

Kissinger became the object of criticism, as well, on the grounds of insufficient attachment to the protection of human rights. This he demonstrated, according to his critics, by dealing extensively and often cordially with the communist dictatorship in Moscow during détente and by supporting the government of Pakistan in 1971 in its bloody repression of what was then the eastern part of the country, which seceded in that year to form independent Bangladesh. In those and other, similar cases he was carrying out policies that served the American national interest as he understood it. He was neither the first nor the last senior policymaker to give priority to the protection of the nation’s interests over the promotion of its political values.

The policies he carried out toward China, and his publicly favorable attitude thereafter toward the communist rulers of that country, have also attracted their share of criticism. His praise of the two principal Chinese officials with whom he dealt, the supreme leader and chairman of the Communist Party Mao Zedong and the prime minister Zhou Enlai, now seem jarring when juxtaposed with the portraits western sinologists and some Chinese observers have painted of the two men as, respectively, a cruel mass murderer and his obliging, sometimes toadying servant. In addition, it has been suggested that Nixon and Kissinger might have done more to affirm American support for Taiwan’s right to determine its own future, although it is worth noting that in 1972 the island was governed in authoritarian fashion and had not yet become the democracy it is now. The rapprochement with China seems less a geopolitical master stroke today, when the People’s Republic has become America’s principal global rival, than it did half a century ago. Nixon and Kissinger undertook it, however, to counterbalance America’s major adversary of that era, the Soviet Union. They were responding to the most immediate and urgent threat that their country faced, as statesmen must.

Just where Henry Kissinger’s reputation will stand one hundred years from now cannot, of course, be known; but it is safe to predict that he will continue to be regarded as one of the leading figures in the history of American foreign policy. This will be so not only because of his accomplishments in office but also because of his prolific, widely read, and highly influential published writings. Uniquely among Americans, he has contributed to the theory as well as to the practice of foreign policy.

His first book, A World Restored, for example, a study of the Congress of Vienna of 1815 that ended the Napoleonic Wars, remains a valuable appraisal of that major event in European history. His memoir of his time in office, set out in three monumental volumes, is written from his own point of view and thus does not constitute the last word on the foreign policy of that period; but these books are and will continue to be the indispensable starting point for any understanding and assessment of that era.

His writings have kept him at the forefront of public discussion of international affairs in the decades since his public service ended. Indeed, in all of American history perhaps only John Quincy Adams has exercised comparable influence after his term as secretary of state; and unlike Kissinger, who has been a private citizen since 1977, after leaving the State Department Adams went on to serve as the nation’s sixth president and then as a leading voice against slavery as a member of the House of Representatives.

Unlike the relentlessly sober Adams, moreover, Kissinger is possessed of a keen wit. “Nobody will ever win the battle of the sexes. There is too much fraternizing with the enemy” and “Eulogies are not given under oath” are among his sayings that will outlive us all.

It is worth recalling, finally, his personal history. He arrived in the United States in 1938 as a fifteen-year-old refugee from Nazi Germany. He served with courage and distinction in World War II, earning the Bronze Star. Henry Kissinger’s 100th birthday thus offers an occasion to celebrate not only his own extraordinary career but also the contributions that the “greatest generation,” whose bravery and sacrifices saw the country through its greatest military trial, have made to the United States of America and to the world beyond its shores.

Michael Mandelbaum is the Christian A. Herter Professor Emeritus of American Foreign Policy at The Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, a member of the Editorial Board of American Purpose, and the author of The Four Ages of American Foreign Policy: Weak Power, Great Power, Superpower, Hyperpower, (2022).

Image: Then Secretary of State Kissinger with President Gerald Ford on the train to Vladivostok on their way to the 1974 Vladivostok Summit. (Wikimedia)

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe