Decisive Battles, Past and Present

The ongoing battle between Ukraine and Russia in Ukraine’s Donbas region recalls three great battles in the history of the United States.

“Great battles, won or lost,” Winston Churchill wrote in the third volume of his biography of his great ancestor the Duke of Marlborough, published in 1936, “change the entire course of events, create new standards of values, new moods, new atmospheres, in armies and in nations, to which all must conform.” Wars can change the course of history and great battles often decide wars. The battle between Russia and Ukraine for control of the area in eastern Ukraine known as the Donbas has the potential to be such a battle.

If the Russian army prevails, it will consolidate its hold on a substantial part of a neighboring country and perhaps use it as a base for a further attempt to conquer all of Ukraine, or be encouraged to invade other neighbors, or both. If the Ukrainian forces emerge victorious, on the other hand, they will not only have saved their country, they will also have administered a severe, perhaps fatal, blow to Vladimir Putin’s aspiration to overturn the post-Cold War European security order and recreate as much of the Soviet Union and the Soviet empire as he can.

The concept of the decisive battle, once a familiar one, has gone out of fashion, especially in the United States. That is no doubt because, for all the occasions on which American troops have been ordered into harm’s way in recent decades, they have fought relatively few battles and no decisive ones.

That was not the case, however, in American history before 1945. The United States waged three nation-defining wars in that period. The Revolutionary War from 1775 to 1783 secured independence for the United States. The Civil War from 1861 to 1865 determined that that independent country would be predominantly industrial and free of chattel slavery. World War II paved the way for the global role America has played ever since. In each of the three conflicts one particular battle proved decisive in the way that the struggle for the Donbas may, although it was not always the battle best known to history.

The best-known battle of the War of Independence took place at Yorktown, Virginia, where a combined French and American force, with the help of a French fleet offshore, trapped a British army led by Lord Charles Cornwallis and secured its surrender on October 19, 1781. That British defeat, however, need not have ended the war. British forces retained a powerful position in North America and King George III favored fighting on.

The government in London, however, wanted to extricate Britain from the North American conflict in order to be able to concentrate on the wider war with France of which the American conflict had become just one part, a war in which larger British interests were at stake than retaining the country’s North American colonies. Benjamin Franklin’s skillful diplomacy persuaded London that it could only achieve this goal by granting the colonies independence, and so it did with the Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783. It was the French connection that made independence possible, and that connection came about because of the result of an earlier battle, at Saratoga, New York.

A British army led by General John Burgoyne arrived there in the fall of 1777 having moved south from Canada on a route passing along Lake Champlain and down the Hudson Valley. His objective was to cut off New England from the other colonies, with the expectation that this would bring the rebellion against Great Britain to an end. Burgoyne’s army encountered logistical difficulties and harassment by American irregulars on its march south. At Saratoga, the British troops met an American force commanded by General Horatio Gates. For the first time in the war, the Americans got the better of the fighting in a major battle. On October 17, Burgoyne surrendered.

Saratoga proved to be decisive in the Revolutionary War because the victory there crystallized a decision by the government of the French monarch Louis XVI to enter the war formally on the side of the American colonies. The French entry transformed the conflict, turning it from one to which the weaker Americans had to devote all their efforts to avoiding losing into one that, with a major assist from the French, they could hope to win and ultimately did win.

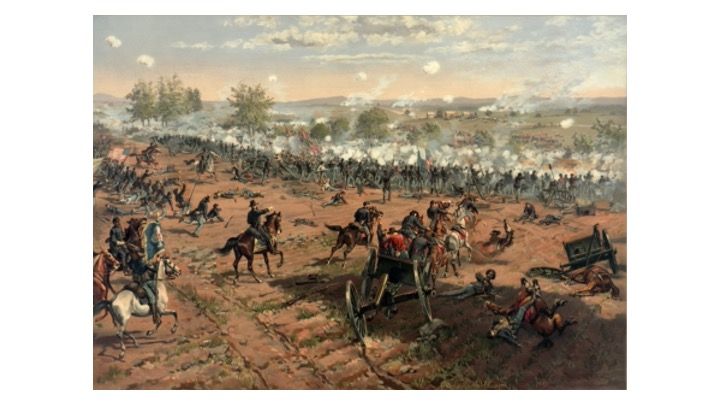

The decisive battle in the Civil War was the engagement fought at Gettysburg, in southern Pennsylvania, over the first three days of July in 1863. There the Union’s Army of the Potomac stopped the advance into Union territory of the Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Gettysburg is the best-known battle of the Civil War, in no small part because of the address that President Abraham Lincoln delivered there on November 19 of the same year, a speech that generations of American schoolchildren have memorized.

Also well known—in the past if not now—were several of the crucial features of the Battle of Gettysburg: the heroic defense of Cemetery Ridge by Union soldiers from Maine and Minnesota, for example, and the courageous but militarily disastrous charge at the Union center by troops under the command of the Confederate General George Pickett.

Gettysburg marked the failure of the Confederate strategy for winning the war. Victory did not require conquering the Union but rather doing well enough on the battlefield to cause the North to abandon its goal of conquering the South and forcing the Confederate states to rejoin the Union. A success by Lee at Gettysburg might well have achieved this goal. It certainly would have crippled the Union Army, demoralized the public in the North, and enhanced the doubts many Northerners had about paying the costs of pursuing the conflict to victory. Lee’s defeat put the kind of victory the Confederates had envisioned out of reach. Two more bloody years of fighting were yet to come, but Gettysburg ended Lee’s string of battlefield victories, the South never regained the military initiative, and Union morale remained high enough to sustain the war to its conclusion.

In World War II, the crucial battle took place on, under, and above the Atlantic Ocean. The Atlantic formed the lifeline of the anti-German alliance. The military and civilian supplies on which America’s allies Great Britain and the Soviet Union depended passed across it by ship. The Germans attempted to sever this lifeline by sinking the ships, using their fleet of submarines known as U-boats. They did considerable damage in 1942 and by early 1943 had reduced the volume of shipping that reached its intended destinations to dangerously low levels. Then, in six remarkable weeks between March and May 1943, the Americans and the British managed to defeat the anti-shipping campaign.

Their success had a number of sources. American shipyards turned out merchant ships and anti-submarine platforms—escort carriers and surveillance and bomber aircraft—in impressive numbers. The Allies also improved their ability to track the movements and locations of the U-boats. Air cover was crucial for the safety of the ships but the Allies were plagued by a “mid-Atlantic gap,” a stretch of the ocean that land-based aircraft could not reach from either North America or the British Isles. The Allies closed the gap by adjustments to some aircraft that extended their range.They also devised more effective anti-submarine devices, notably depth charges that exploded under water.

These developments reduced the German U-boat attacks to tolerable—and ultimately negligible—levels. If the Allies’ efforts had failed, they could not have prevailed in Europe when they did, if they could have prevailed at all. Control of the Atlantic was the necessary condition for the Anglo-American invasion of France on June 6, 1944, and the subsequent drive to Germany that, in combination with the Soviet assault from Germany’s east, ultimately forced the Third Reich to surrender.

These three decisive American battles have some features in common with the fighting in the Donbas and the larger conflict of which it is a part. Like the thirteen colonies in the Revolutionary War, Ukraine is fighting for its sovereign independence. Like the colonies in that war and the Confederacy in the Civil War, it is the weaker party and is not seeking to conquer Russia, but only to evict Russian troops from its territory. Ukraine is fortunate in receiving assistance from third parties; similarly, the colonies attracted allies and won while the Confederacy failed to do so, despite efforts to gain support from Great Britain, and lost. In the 20thcentury, moreover, the three great American victories—in the two World Wars and the Cold War—came about when and because the country had major allies.

Finally, the United States and Great Britain won the Battle of the Atlantic because of their superior technology, and it is the superior military technology with which the United States and NATO are furnishing Ukraine’s forces that gives those forces a fighting chance against Russia. In the current war, as in World War II, the United States is playing the role that President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced in the earlier conflict: that of “the arsenal of democracy.” If the battle for the Donbas turns out to be a decisive success for Ukraine, it will be American and NATO weaponry, supporting the bravery and the ingenuity of the Ukrainians, that will have made it possible.

Michael Mandelbaum is the Christian A. Herter Professor Emeritus of American Foreign Policy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, a member of the editorial board of American Purpose, and author of the new book The Four Ages of American Foreign Policy: Weak Power, Great Power, Superpower, Hyperpower, from which this essay is adapted.

American Purpose newsletters

Sign up to get our essays and updates—you pick which ones—right in your inbox.

Subscribe